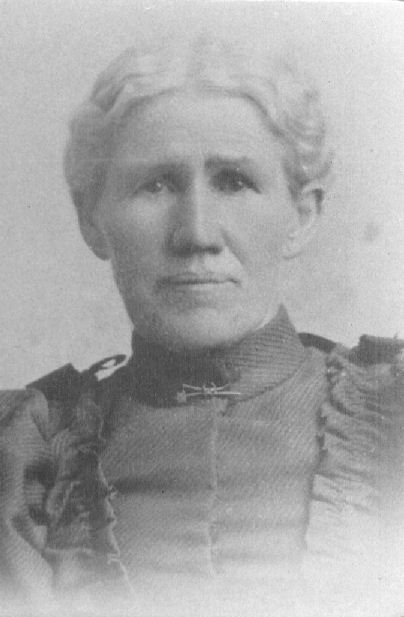

Christina Brown

2 July 1844 – 22 May 1924

Between

1800 and 1900 Scotland changed from an agricultural society to one of

large urban centers with massive factories and heavy industry. Vast

numbers of Scots still worked in agriculture and fishing but the

textile, coal and shipbuilding industries attracted more and more people to the cities.

The heavy industries – coal mining, iron, shipbuilding, and steel – made the central belt of Scotland one of the most industrialized places on Earth. Scotland built half of the ships in Britain and a quarter of all the world’s train locomotives.

James Watt’s steam engine powered the Industrial Revolution. The power-looms of Scotland’s cotton mills changed the textile industries forever. The Industrial Revolution allowed cheaper and more plentiful goods to be produced, but at a social cost. Children, boys and girls, usually had no choice but to follow their parents into factories or mines for work.

Many people, including children, died in accidents in Scotland’s coal mines, foundries, mills, and railways. Workers faced long hours and poor conditions, toiling for 50 to 60 hours a week and children were beaten to make them work faster. The Factory Act of 1833 prohibited employment to children under the age of 9, with meal breaks of an hour and a half per day, holidays of two full days and eight half-days per year, and education for those who worked part-time.

The incredible success of James Watt’s steam engine greatly increased the demand for coal. Many Scottish coalfields were opened up to provide coal to generate steam. Large-scale industrial mining dug deeper and deeper into underground coal-seams to meet the huge demand. Women bearers carried heavy baskets of coal up to the surface, and children heaved sleds laden with coal. Pit ponies dragged heavier loads but they were more expensive to keep. Finally, the Miners Act of 1842 forbade the employment of women and girls underground; no boy was to work until aged ten.

Of those who

worked the coal mines was Robert Brown (15 Sep 1816) of Boreland,

Fife, Scotland. At the age of 21 he married Elizabeth Beveridge (23

Sep 1815) on November 4, 1837 at

Dunfermline, Fife, Scotland. Their first children, twins Janet and

David, were born in 1838 but died as infants. Their next child,

George, born in 1839 also died as small child. After having and

loosing three children, Janet was born on October 27, 1841. Then on

On July 2, 1844 Christina and her twin sister, Marion, were

born in Halbreath, Fife. Scotland. This is the story of Christina

Brown.

Christina's twin

sister, Marion

After Christina and Marion, four more children were born; Elizabeth who was born and died in 1846, David on April 8, 1847, Robert Jr. on October 20, 1850, and Elizabeth on November 17, 1854.

When Christina was two years old, her father and mother were converted by and Elder Peacock from Mann, Utah and were baptized into the Mormon Church: Robert on August 29, 1846 and Elizabeth more than a year later on September 13. 1847.

Christina was baptized at the age of nine by Elder Mark Lindsay in 1853. She was baptized at two o'clock in the morning. This was necessary because of the persecution being heaped upon the saints of that section. They had to walk about eight miles both to and from the place of baptism. The Elders had prepared a place in a small stream of water made deep enough by damning the stream with rocks.

The family moved often as her father was constantly changing jobs. When he found a better job he would start immediately and quit his old job without leaving notice. He would tell his wife, Elizabeth, to have things packed and he would send for her and the children to join him.

He loved the sea. At one time he moved the family to a large seaport where they lived in a third floor flat. The town was protected by a 30 foot high rock seawall to keep back the tide and storm surges. This wall was 14 feet thick at the base and 3 feet at the top and had gates every so far apart so people could go down to the shore.

When Christina was a girl, she and her friend Kate would run away from school and go to the beach. They undressed and laid their clothes a ways back on the beach and then would swim in the ocean. They would get so busy playing and the first thing they knew their clothes were floating in the water as the tide was coming in. They would ring them out and put them back further and the same thing would happen again two or three times. When they thought it was about time for school to let out they slipped back to the school and waited for their sisters to come out and then would bribe them not to tell their parents.

Christian's father had sailed to South America with a load of coal and while he was gone there was a terrific storm. The sea lashed the seawall and almost came over the top. Christina and some other kids got up on top of that wall and ran along chasing one another while the tide was dangerously high. If one of them had fallen in, it would have been goodbye. The pressure of such a high tide broke open one of the large gates and flooded the town. Everyone that lived in the lower flats had to dash up the stairs. Her father had been gone for 14 months and everyone thought that the ship had foundered and was lost. To their great surprise, one day it sailed into port. They had a big celebration to welcome them home. He had nearly lost his life in the storm.

Christina had very little schooling. At the age of nine she went to work in the coal mines loading cars. When she was in her teens she worked in a linen factory where she learned to weave. She used to weave beautiful tablecloths. She also worked in the paisley factory where she learned to weave beautiful paisley shawls.

At the age of 18,

Christina left Scotland to emigrate to Utah. She traveled in

company with her sister Janet, Janet's husband, Thomas Adamson

and his father. They boarded the 1,350 ton packet

ship “Cynosure” (French for Ursa Minor) in company with 775

Mormon emigrants bound for Utah with Elder David M. Stuart

presiding.

The ship got underway about 5 a.m. on Sunday May 31, 1863 and sailed down the Mersey River and into the Irish Sea. A misty, drizzly rain was falling, making it very disagreeable on deck. The weather cleared off about 9 a.m., when the sun came out. During the first few days of the voyage some seasickness was had among some of the passengers.

On June 9th, Christina's sister, Janet, had a baby girl who they named Elizabeth Cynosure Adamson.

Midway through the trip, there was an outbreak of measles among many of the children and even a few adults. Ten or eleven children died as a result of the measles. For the most part, the weather was favorable for sailing, encountering an occasional squall. The only real problem was a dense morning fog as they sailed the North Atlantic and along the Outer Banks of Newfoundland. The fog usually lifted as the morning passed. One morning, they found themselves in the midst of fourteen icebergs, sailing close by one of them. It looked like a little island and created quite a curiosity among those on board.

On the afternoon of July 16th the fog cleared away and they saw land for the first time since the 2nd of June. They were immediately off Block Island, east of Long Island. Two days later the ship approached the Sandy Hook Lighthouse where about 8 p.m., it anchored for the night. The next morning at 5 a.m. the ship weighed anchor and proceeded up the North River. At 9 a.m. a steam tug took it in tow; all the Saints were mustered on deck and at 10 a.m. a doctor came aboard to examine the passengers to determine if they were in good health. He was through by 11 o'clock and left the ship which proceeded on its way. At noon the Cynosure dropped anchor off the Battery in New York Harbor. The passage took 49 days, 28 of which there had been a constant succession of fog and calm winds.

Upon leaving the ship on July 20, 1863 New York City was in chaos as ten thousand soldiers were there from the battlefront to enforce the draft. Castle Garden was in a state of turmoil when they landed, and they were hustled like so many sheep into a pen.

From New York

they traveled up the Hudson River to Albany, New York and boarded a

train for Chicago. They arrived on the morning of the 27th and they

were immediately put into cattle cars, as the passenger cars were

being used for the transport of troops. From Chicago they boarded

another train bound for Quincy, Illinois where they transferred to

yet another train which took them to St. Joseph, Missouri.

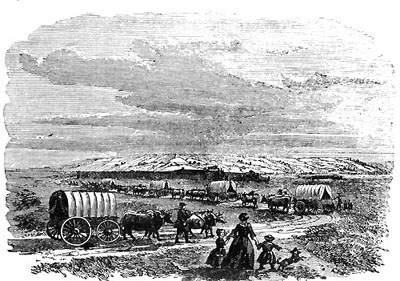

On the 29th of July they boarded a riverboat that took them up the Missouri River. On August 1st the arrived at the staging camps at Florence, Nebraska where they stayed for two weeks before setting out across the plains. Wagons, ox teams, and teamsters had come from Utah as part of the Perpetual Emigration Fund with the purpose of transporting the emigrants to their new homes in the mountain valleys of the Great Basin.

Christina and the Adamsons were part of the Samuel White Company, with about 300 individuals in the company when it started out on August 15th. The trip across the plains was a difficult ordeal. On the afternoon of the fourth day on the trail, a thunderstorm moved in. The storm had been raging for about a half an hour when a thunderbolt broke immediately over the wagon train. Of a team of three yoke of oxen, five were struck dead on the spot. The team happened to be at the point were the telegraph wire crossed the road. The lightening entered the wagon, set some hay on fire and then traveled along the chains to the cattle. On seeing the wagon on fire, great concern arose as there were several hundred pounds of gunpowder in the wagon. The teamsters quickly removed the contents of the wagon and all danger was removed. The train moved on about 500 yards from the scene of accident and camped for the night. No one was hurt or injured by the storm although several were somewhat stunned. It continued to thunder and lightening all night.

Christina, who had just turned nineteen, often walked ahead of the wagons with some other young ladies. To pass the time, they would sing. One of the teamsters, who happened to be Mortimer Wilson Warner, was pleased with her singing and asked her if she would ride with him for a while and sing to him. She did, and romance blossomed on the plains. From then on, they saw each other often as the days passed into weeks.

Among some of the many hardships they encountered, several of the children who came down with measles on the ship died. Once while crossing the Platte River, one man had his arm chewed badly by a bear.

But there were also the good times. They often stopped to let the oxen rest, shoe them, mend the yokes, and make general repairs. The women took this time to bake bread and do laundry. They sometimes rested a few days when they found a stream of water with good grass for the animals.

One afternoon

toward the end of September, one of the older women went down below

camp to investigate some red berries and find out what they were. She

came running back to the camp and said there was a big black beast

down in the bushes. Every man grabbed his gun and made a wild dash

for the berry patch. The big black beast was found to be a huge

black bear and the men all wanted to get him. The grass was tall in

the berry patch and the bear had trails all through the grass. Upon

finding him, they all started to shoot at it. This made the bear

angry and harder to kill. They really had a time. He would come out

on one trail and dart into another when one man shouted, "Here

it is!" Then they all ran for that side and the old bruin would

make a pass for the nearest opening in sight. When one of the men

passed by the opening where Mr. Bear was, it made a pass at him and

hooked him by the seat of the pants, taking the whole seat out of

them. They finally killed the bear, dressed him, and hung him to a

telegraph pole. Then all the fiddles and concertinas (a small

accordion) were brought out. They built a big bonfire and danced

until midnight. They danced Scottish Reels, Quadrilles, and

Shottishes and called it the Bear Dance. They divided the meat among

all.

Finally,

on October 15, 1863 she reached the Salt Lake Valley, five months after

leaving her home in Scotland. Christina was only there a short time

before she married Mortimer on February 29, 1864 at Fillmore, Utah.

There they made their home where Mortimer farmed and ran a blacksmith

shop. She gave birth to their first child, Christina Delilah on December

19, 1865 and a second daughter, Elizabeth Ellen on November 8, 1866.

Her parents and younger brothers and sisters emigrated to Utah in 1866.

Mortimer

While living in Fillmore, the Utah Territory was involved in the Black Hawk War. The Ute Indians would steal the pioneer's cattle and raided homes for anything they could get a hold of. Many settlers were killed by the Indians. When these raids occurred, Mortimer with other men were called out in the night. The grabbed their guns and went out to chase them away.

When the men were called out to fight, the women would go to each other's homes for protection and to sleep. One night when Mortimer was out on a chase, it was raining and so dark you could not see your hand before you. Christina had three little ones and went to be with her sister-in-law, Cornelia. There were about a half dozen women and their little ones gathered together. They had quilts hanging up to the windows so the light from the fireplace could not be seen. All of a sudden they heard someone scratch on the window and then on the door. Everyone was petrified! There was hardly a man left in town so they knew it must be an Indian trying to get someone to come out. Then someone started laughing and knocked on the door and asked them to let her in. It was Cornelia's mother.

They moved to Kanosh, Utah (about 15 miles south of Fillmore) where their first son, Mortimer Wallace on January 29. 1869 Later that year on October 5, 1869 Mortimer and Christine journeyed to Salt Lake City and together received their endowments and were sealed in the Endowment House. Four more children were born while the lived in Kanosh. Robert Orange, was born on March 6, 1871; Lonevie was born on June 17, 1873; and Janette on October 17. 1875. Cornelius was born on March 14, 1878 just prior to their moving to the Circle Valley where they lived in the United Order at Kingston.

In Kingston, the whole community lived as one big family, living a happy contented life. Everyone ate in a large dining hall which was divided so the adults ate in one section and the children in another. However, they slept and lived in their own homes. The men each had certain work to do, for some would farm, others take care of the sheep, etc., always working in a body. At that time, the farmers cut the wheat with cradles when harvesting. About three miles above town all the dairy work was done and the butter and cheese brought down in large barrels for use in the winter time.

The women worked

on two-week shifts at cooking and taking care of the children. The

girls waited on the tables two weeks at a time and took care of the

children when the women were cooking. Christina was the assistant to

the head cook responsible for overseeing the kitchen. The menus were

simple with little variation, except for meat. For breakfast;

potatoes, bacon and eggs, milk, and fruit (when it was available),

mostly wild berries and dried apples. In the summer they had

breakfast at six o'clock.

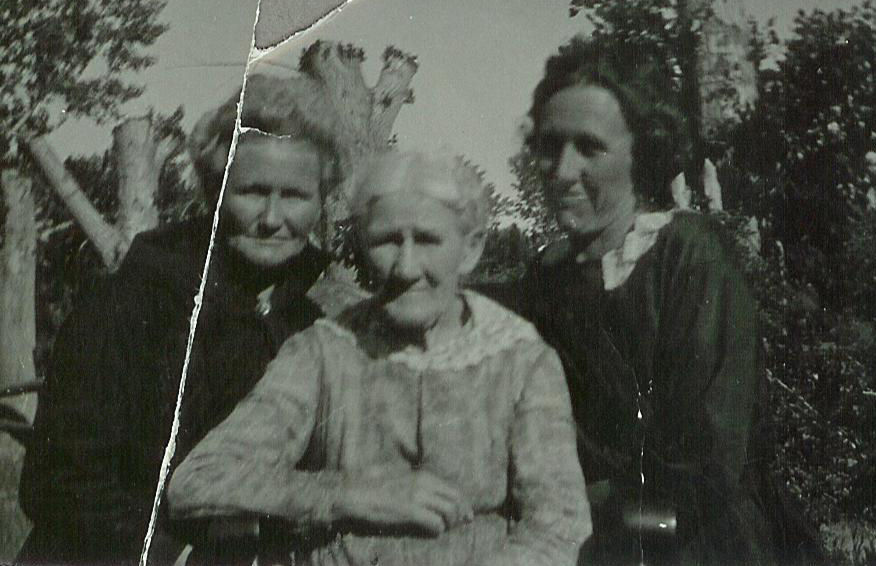

Janette Warner Day, Christina, and LaVina Warner Alger

The dinner horn was blown at 11:00 o'clock so the men could take care of the horses and prepare for their noon meal. The horn came from the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) and could be heard for three miles. Only two men there were able to blow it. Dinner consisted of boiled vegetable and beef soup which was a favorite, pork, mutton, or sometimes fish from the Sevier River, potatoes and gravy, vegetables of all kinds, dry beans, and hominy, simple puddings and sometimes pie or cookies. Pies were usually baked only at conference time and for social events by the men who made all the bread. For supper they had cornmeal mush and milk, with no sugar. Minute pudding (flour mush with sugar, cinnamon, and milk) was a rare treat.

When a meal was late, the cooks hoped a certain gentleman would be called on to pray because he gave such lengthy prayers which gave them a little more time. When it was all ready they hoped that he wouldn't be called on because then it would get cold.

Each week, two of the smaller boys were chosen as chore boys for that week. They chopped wood, carried water, took out the ashes, and did other kitchen chores.

While living in Kingston three more children were born. Twins Mary and Marion where born March 1, 1880. Marion died a week later. On June 1, 1882 a son, Dorus, was born.

In 1883, upon recommendation of the authorities of the Church, the United Order was brought to an end. The property was divided up and people began moving away. It was probably in 1882 or 1883 that Mortimer and Christina moved their family to Coyote and settled in the mouth of Black Canyon. There Mortimer and Christina spent most of the rest of their lives and raised their large family. They had two more children while living in Coyote: Adelia was born March 26, 1884 and died two years later on March 13. 1886, and Lavina, who was born on March 22, 1887.

When

Mortimer and Christina first moved their family to Coyote they lived

across the river from the main farm. During the spring runoff, the

river ran high for a month or sometimes more. They couldn't get to

town unless they swam the horses across, pulling the wagon. One time

Mortimer had to go to town for supplies and groceries. At that time

the river was particularly high and Christina was frantic as she saw

him coming home. The whole family ran down to the river bank to see

how he was going to get across. He had to go farther upstream and

swim the horses downstream so they could come out at the landing. He

started the horses into the stream and the water came into the wagon

box so he had to put the supplies up onto the spring seat. About

half way to the landing, the wagon box floated off the carriage frame

so Mortimer let loose of the lines. The horses went on across the

river. Mortimer went on down the river in the wagon box. Christina

screamed, “Heavens Mort, where are you going?” He stood up in the

box and waived his hat and said, “Going down the river!” The

boys ran to the corral and got a long lasso rope and threw one end

out to him as he drifted by. He caught hold of the rope and fastened

it to the brake leaver and they pulled him to the bank. Christina

said, “I’m not going to live on this side of the river any

more.” So as soon as the flood season was over, they moved the

house across the river.

Christina standing in front of their home in Coyote

Christina was a

devoted wife, mother and a diligent midwife. who was always ready to

help with any need. She was a visiting teacher and first counselor in

the Relief Society Presidency. She was the mother of twelve children,

ten of whom she raised to maturity.

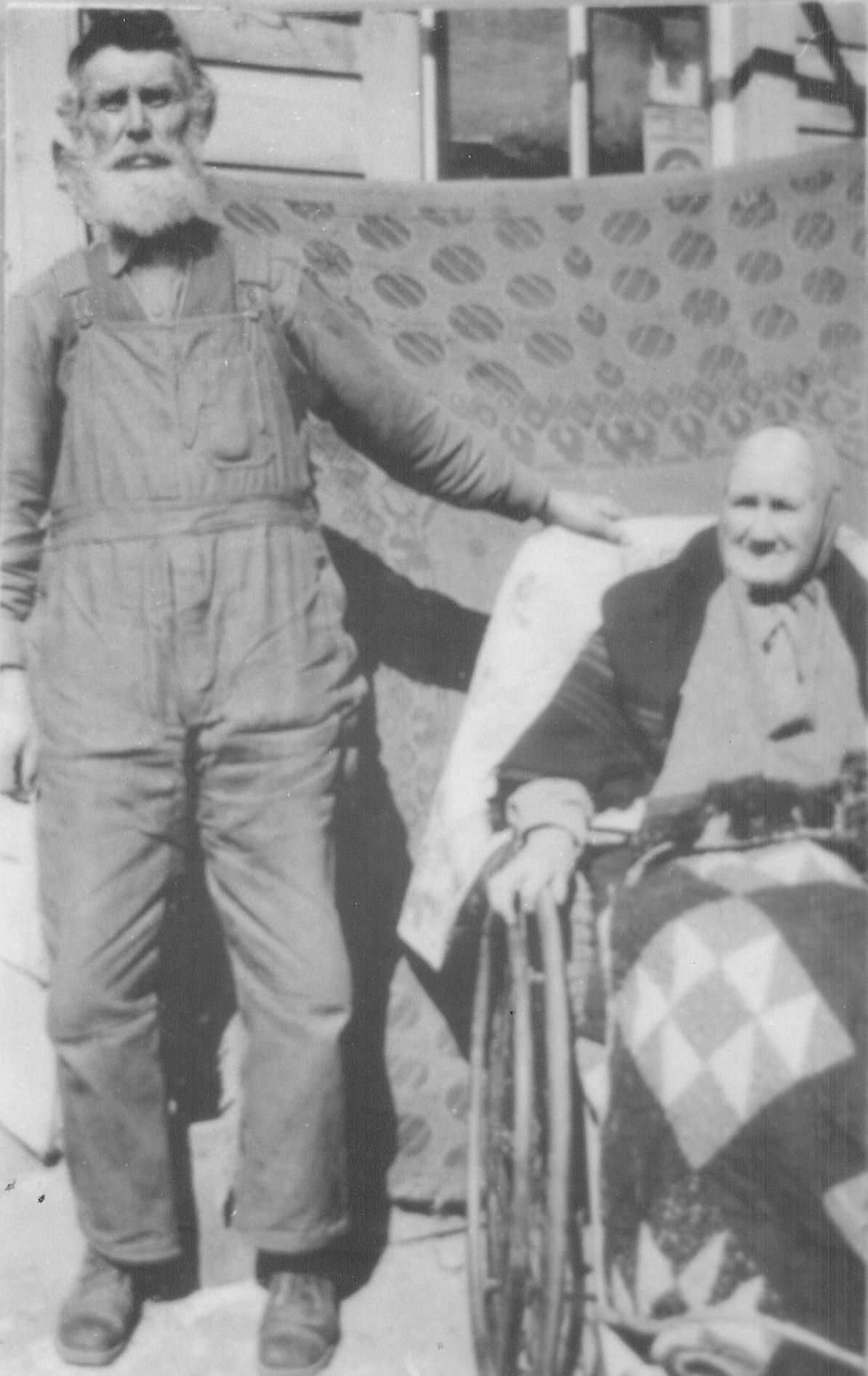

Mortimer and Christina

in later years

In about 1910, Mortimer sold their place to Neil Warner and he and Christina moved to Junction, Utah where they lived a number of years. Christina was a Relief Society teacher for eight years. It was at this time that Christina injured her back and was forced to spend the rest of her life in a wheelchair. She finally got so she could get around on crutches. In later years, about 1918, they moved back to Coyote and spent the remaining years of their lives there. They lived with their daughter, Janette and her husband, Daniel Day who had a home on Poison Creek. It was here that Mortimer died on August 14, 1921 at the age of 79. She followed him three years later on May 22, 1924 at the age of 80. She was buried in the Antimony Cemetery next to her beloved husband. At the time of Christina's death she was survived by one brother, nine children, 75 grandchildren and 89 great grandchildren.

Sources of information:

The bulk of this story comes from an uncredited life story of Christina Brown Warner, most likley by Lavina Warner Alger.

The Introduction is from “Scotland's History” at www.ltscotland.org.uk

Christina's life in Scotland and the story of the wagon box floating away are from letters from Lavina Warner Alger, her daughter, to Ira Frost

The voyage of the Cynosure and the journey to Florence, Nebraska are from journal exerts found at http://www.lib.byu.edu/mormonmigration/voyage.php?id=110&q=Cynosure

Some details of crossing the plains are from journal exerts found at http://www.lds.org/churchhistory/library/pioneercompanysources/1,16272,4019-1-316,00.html