|

Peter Sheffield

Barson

12

February 1849 – 12 November 1942

A hundred years is only a blink of an eye in the grand scheme of

things, yet it is a longtime in a person's lifetime. Most people

don't live nearly that long, but some come quite close. Peter

Sheffield Barson lived a long life of ninety three years and nine

months. During his lifetime he witnessed marvelous things as they

came about.

His

story actually begins with a young shoemaker in Wellingbourough,

Northampton-shire, England by the name of Samuel Barson. Samuel was

born in Wellingbourough on July 15, 1825. At the age of eighteen he

joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day saints. In his

association with other members of the Church he became acquainted

with another young convert from Wellingbourough, a dressmaker by the

name of Ellen Sheffield. In time, they were married on December 26,

1846 and made their home in Wellingbourough.

Their

first child, Orson Pratt was born on October 15, 1847. Peter was born

on February 12, 1849 in Wellingbourough. Sadly, his brother died four

months after Peter was born. John was born in 1850 and Sarah Ellen on

February 18, 1851.

Being

a Mormon in England during those days was not a very popular thing to

be. Persecution was very severe and Samuel and Ellen longed to

immigrate to Utah and unite themselves with the main body of the

Church. They worked and saved everything they could to prepare for

the long journey.

With hearts full of faith, they embarked on what would prove to be a long

and arduous journey. On Wednesday, February 22, 1854, the ship

Windermere sailed from Liverpool with 460 passengers, all Latter-day

Saints; including Samuel age twenty eight; Ellen age twenty seven,

Peter age five, John age four, and Sarah age three. On the two month

voyage they encountered a terrible storm, a fire a board the ship, a

small pox outbreak, and a period of no wind which stranded the ship on

the high seas. The Windermere arrived at New Orleans 23 April, 1954.

Samuel, Ellen, Peter, John, and Sarah had survived the perilous voyage,

but there

was still a long ways to go.

After a few days in New Orleans, the Barson family continued their journey

and traveled up the Mississippi River by steamboat. While sailing up

the river, cholera broke out. Ellen Sheffield Barson was stricken

with the disease and died on May 15, 1854 at the age of twenty seven.

At the next stopping place, her body was taken ashore and she was

buried on the banks of the Mississippi River.

With

saddened hearts, the father and his three little children journeyed

on to St. Louis, where Peter's Grandfather Sheffield lived. He had

immigrated to the United States sometime earlier. He persuaded

Samuel to leave his two smallest children, John and Sarah, with him

now that their mother was taken. Samuel consented, with the

understanding that he would send for them later. At that, he soon

continued on with Peter. From St Louis, the two of them traveled up

the Missouri River on another steamboat to Westport, Missouri near

Independence to the staging areas for wagon trains bound for Salt

Lake City.

At Westport, they joined the company of Captain Darwin Richardson. On

June 17th the company moved out with about three hundred people and

forty wagons. At five years old, Peter and his father walked across

the plains to their new home. On the trail the encountered large herds

of buffalo and hostile Indians.Finally,

on the last day of September the Richardson Company arrived in Salt

Lake City. It had been a long journey for Peter and his father, one

fraught with peril and loss. They had not been in Utah long when

their hearts were saddened with the news that the John and Sarah who

had been left in St. Louis had died.

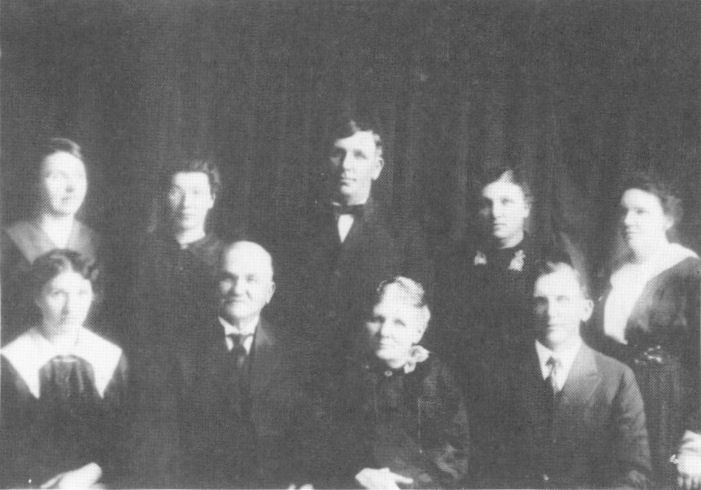

| |

Peter at age 12 |

Samuel and Peter made a new home for themselves all alone in a new land.

After arriving in Salt Lake City they lived with Bishop Tingey until

Samuel found work. Samuel Barson was a shoemaker and soon as given

employment with the Jennings Company.

Sameul married Sarah Ann Jennings on October 25, 1855 and home life

was established again. Ann was a twenty two year old convert from

Yorkshire England. Their first child, who they named Samuel, was born

and died on January 9, 1858.

During

the winter of 1857-58 the Saints were ordered to leave Salt Lake City

and move south because of the coming of Johntson's Army. Accordingly,

Brigham Young directed all of the people north of Utah County to

leave their homes and proceed southward, Thus began the "move".

During the spring of 1858 thirty thousand people migrated southward.

When the crisis was passed they were able to return to their homes.

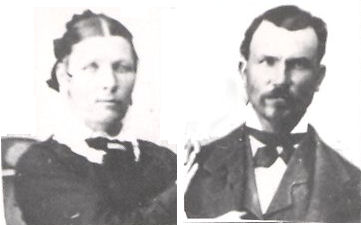

Samuel Barson - 1861 | |

Soon after Samuel Barson was blessed with more means and he bought a lot and a one room adobe house.

Two more children were born to Samuel and Ann: Martha Jane on March 15, 1860

and John William on December 15, 1862.

When

Peter was sixteen years old, his father died on August 25, 1865 at

the age of forty years old. Not long after that, Ann remarried and

and left the territory, and the church. and she took Martha and John

with her and moved to Cherokee County Kansas near Joplin, Missouri.

Martha died at age thirteen, but John went on to become a doctor. The

day they left, Ann had handed Peter fifty cents, climbed in the

stagecoach, and left him to face life on his own.

Left alone, Peter lived wherever he could get work. He worked many a day for fifty cents and boarded himself. He had no other family in the territory. His uncle, John Sheffield and his wife both died while crossing the plains in 1855. Life moved on for Peter in spite of his loneliness.

In 1866 , When Seventeen years of age, Peter S. Barson and William Curtis

and others were called by Bishop Samuel Wolley of the Ninth Ward to drive

four yoke of oxen and a wagon to go back to Missouri and return with a company

of emigrants in the Captain Joseph Rawlins Company. They traveled between

fifteen and thirty miles each day. The oxen would get very tired and when they

would stop a few minutes the oxen would stick their tongues out while laying down.

Over four hundred individuals and sixty five wagons were in the company when it

began its journey from the outfitting post at Wyoming, Nebraska (the west bank

of the Missouri River about 40 miles south of Omaha) on August 2nd. On the way

back the men and boys agreed that the first one to grumble at the cooking had

to be the cook. The company returned to Salt Lake City on October 1, 1866.

When he was about eighteen during the height of the conflict with the Indians

in about 1867 and 1868, Peter worked as a cook at Fort Douglas. When the army

was called to Battle Creek, four soldiers shook his hand and bade him good bye

saying..."We have a feeling that we will not be back.” Their impression proved

correct and their names are written on the monument at Battle Creek.

Peter kept worrying about Mormonism and wondering if it were true. He

wished that he could ask his father. One night as he was lying on a

lounge thinking and pondering over religion, a light appeared in one

corner of the room. In the light he saw his father clothed in temple

robes. Grandfather knew this was his chance, so he asked his father

if Mormonism were true. His father answered, "Yes, but not the

way some people live it.” Peter had said, "If all the world

would go in darkness and people say there was no resurrection, I

would believe in Mormonism and the resurrection, because I have seen

my father." He also said he would have believed in no church if

his father had not appeared.

Peter

caught the attention of sixteen year old Mary Ellen Scott from Mill

Creek and began calling on her. Mary Ellen, the daughter of John and

Mary Pugh Scott, was born on May 22, 1849 in Salt Lake City. She grew

up in a pioneer home in which lived her father, his five wives, and

thirty-six children. This is where she learned to cook, sew, spin,

weave, and tend babies. One Sunday morning Peter walked all the way

out to Millcreek to be with her at Sunday School. He ate dinner with

the family and also stayed for meeting. When about nineteen years of

age, they decided to get married.

Peter had saved three hundred dollars. He worked for Wells Fargo, changing

horses as the fast stagecoaches came through. With no parents or

home, he decided to give his money to Mary Ellen for safekeeping.

Several days later, he thought, "Suppose Mary Ellen should run

off with some other man. What then would become of my money?"

The

thought of losing that money worked on Peter's mind for several days;

until, in desperation, he walked to Millcreek and asked Mary Ellen to

give back his money. She was hurt, but did as he asked. A few days

later, Peter was sent north with freight to Corinne, then a "gentile"

city, notorious for its gambling. Sometimes a reckless surge swept

over him! What did anything matter? There was no one to care.

But

there was Mary Ellen and the testimony of his father that he could

never get away from. It came to him at night, at his work, wherever

he was; always it came, "My boy, Mormonism is true." No, he

would not be deceived.

It

was dusk as he neared Corinne. He had traveled in the dust all day,

and the lights he saw meant food, water and rest. The smells of

alkali and swamp grass mixed with horse sweat penetrated his

dust-plugged nostrils. He cracked his whip and urged his tired horses

on. Music from the bar-rooms floated out to the dusty streets; and as

he looked through the windows, everyone seemed to be having a good

time.

While

he stood there, a sociable stranger took him by the arm and said

genially, "Howdy, stranger. How about me and you havin' a good

time tonight? I suppose you have a little money?" How proud

Peter was to say that he did, and he was at once a member of the

excited crowd, with his newly found friend always suggesting

something more. The jolly, friendly man encouraged him to spin the

"Wheel of Fortune." "Right this way," he called

out. "Come and get rich overnight."

Round and round and round she goes And where she stops nobody knows. Peter

tried the wheel several times; but each time it stopped, his money

was in the wrong place. He shook dice, and he played cards trying to

make more money, but he always lost. As morning broke, Peter counted

his money. He had thirty dollars left. Shame and humiliation crept

over him. How could he get married now, and what would Mary Ellen

think of such a fool? He walked out alone along the banks of Bear

River, sat down, took out his red handkerchief, and wept bitter tears

of self-condemnation.

After

returning to Salt Lake City, he again walked to Millcreek and told

Mary Ellen his story. The loyal girl told him that she loved him just

as much with thirty dollars as With three hundred, and they would be

married just as they had planned.

Peter

asked the consent of Mary Ellen's mother to marry her daughter, but

her father, John Scott was not at home. It would not do to marry

without his consent, so Peter sent a telegram. Mr. Scott replied, "I

will give my approval if first you get the consent of Brigham Young."

Peter ripped up the telegram.

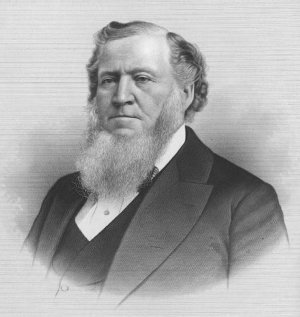

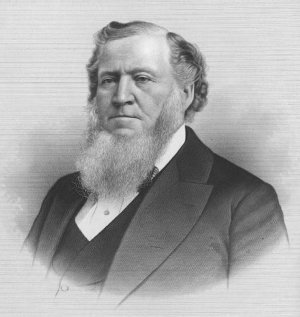

| |

BrighamYoung |

John Scott was an absolute monarch in his own home, and Peter knew he

would have to go see Brigham Young if he wanted to marry Mary Ellen.

A few days later he made the appointment. Peter, decked out in his

Sunday best, knocked at the office door of the president at the

appointed time. A man that looked almost square in stature with sandy

hair and beard, keen gray eyes, and a kindly smile looked out at him.

Peter was surprised to hear President Young ask, "So you are the

son of the late Samuel Barson, the singer?"

"Yes,

sir," Peter began to feel more at ease. "I want to get

married and I must have your consent to please John Scott."

President

Young smiled as he said, "You are ready to get married? Well, go

my boy, and may God bless you." He took a gold-colored pencil

from his pocket and wrote on a piece of paper. "I give my

consent to this marriage. Brigham Young." The interview that

Peter dreaded so much turned out to be a pleasant one. He left the

office feeling more important. Brother Brigham knew him and had been

watching him.

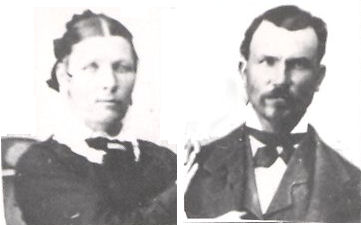

Mary Ellen Scott and Peter S. Barson about the

time they were married.

| |

With this slip of paper to present to John Scott, there was just

one more person to get the consent of, that was his bishop. Peter

knew that marriage was close at hand.

They were married on October 20, 1869 in the Endowment House in Salt Lake

City. At last he would have a home of his own, someone to laugh with,

and someone to love – his own Mary Ellen. At first they made their

home in Salt Lake City, Their first home was in a wagon box while

Peter fenced 160 acres of land for a yoke of oxen.

Their first child, John Samuel, was born

premature on May 14, 1870. He only lived a couple of months and died

on July 28th. Peter by now was well acquainted with the grief and

saddens that comes with the loss of loved ones.

Over

the next few years, Peter and Mary Ellen moved several times. Ever eager to better himself, they moved to Millville, just south of Logan

in Cache Valley. It was here that Hyrum Sheffield was born on August

27, 1871. They next moved back to the Salt Lake Valley to Millcreek

near Mary Ellen's family. Mary Eliza,who went by Liza was born on

January 10, 1873.

| |

Eliza Ann Scott

|

Plural marriage was being practiced at the time and obedient to the

teachings of the Church, Peter and Eliza Ann Scott were married on

August 8, 1875 in the Endowment House by Joseph F. Smith. Eliza Ann

was Mary Ellen's younger sister, also the daughter of John and Mary

Pugh Scott. Eliza was born on October 20, 1852 in Millcreek.

As

a girl, Eliza was in poor health but had more ambition than she had

strength. She had a cheerful disposition, was witty and people

enjoyed her company very much. Eliza loved to entertain her friends

by telling fortunes with tea leaves. She was slender, had dark blue

eyes and beautiful brown hair. Although in poor health, she always

kept busy. When she was too sick to work, she had a hobby of making

flowers from wool or hair. She was also a very good seamstress.

Peter,

Mary Ellen, Eliza, and their family next moved back into Salt Lake

City where they lived in a one room house. Later they moved to

Slaterville in Weber County. It was here that Eliza's first child,

Denny Burdell who went by “Bird” was born on May 11, 1876.

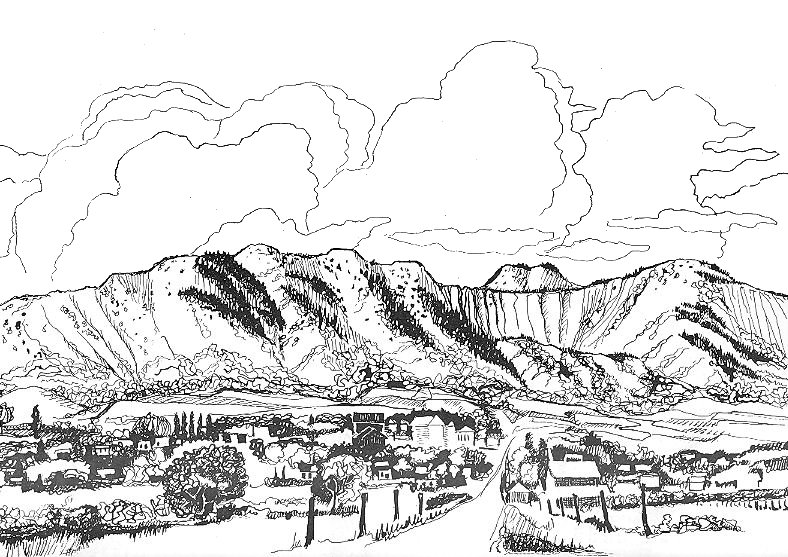

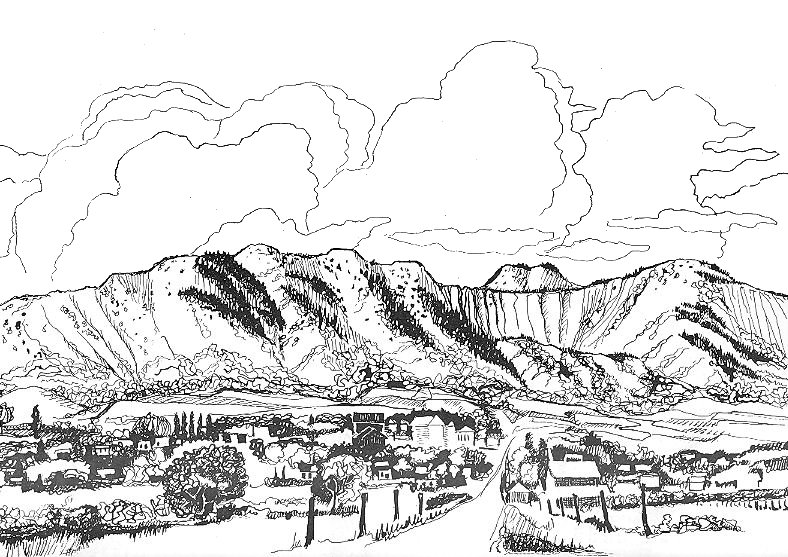

A sketch depicting Clarkston in the early days

looking west with Gunsight in the background | |

In the fall of 1876 Peter traded a thousand board feet of native lumber

and moved his family to Clarkston in Cache Valley. At the time,

Clarkston was still a fledgling settlement and the homes were either

log cabins or dugouts. Their first home in Clarkston was a log house

with a fireplace used for cooking and heat. Homemade candles were

used for lighting. Mary Ellen and Eliza made their clothing from home

spun fabric. Farming was done with hand plows and wooden harrows.

Grain seed was broadcast by hand. It was harvested with a sickle and

cradle. Hay was cut with a scythe and raked with a wooden rake.

Peter

made a trip to Salt Lake in 1879 to buy a plow. When he returned he

brought home with him a small organ, the first one in town. He

learned how to play it and hauled it back and forth to and from the

church. He played for church meetings including the ward choir,

dances, and other entertainment. He also played the violin.

In

some plural marriages the wives lived in separate homes with their

own children. In the case of the Brasons, they all lived under the

same roof. Mary Ellen and Eliza, being sisters had a loving

relationship with each other and the husband who they shared. Their

children all got along well with each other. All in all, they were a

very close knit family. Two more children were born to Eliza. Lucy

Ellen who went by Nell was born on August 20, 1879 and Vilate Scott

who went by Vie was born on January 29, 1882.

The comforts of modern living were appreciated by Peter who, with his two

wives, welcomed improvements as they came along. They had moved

several times and bettered their conditions each time. He became one

of the more prosperous farmers in Clarkston. To them the possession

of land was a means of security, and land was something almost

sacred. Seeing the possibilities in little things, they were anxious

to succeed and were not afraid of hard work.

| |

The Barson home

|

Thus it was that in 1887 Peter acquired 160 acres of land located one and

one-half miles east and a little north of Clarkston where they built

a new two story frame house and he carefully laid out a well-planned

farm. The Barsons had a few cows and made butter which they sent to

Salt Lake for Grandma Scott to sell. From the proceeds they were used

to buy wallpaper for their home.

In summer of that same year, Peter had been in Logan working in the temple all day. After leaving the temple, he was walking down the street in Logan when he was arrested for having been a polygamist. He was taken to Salt Lake City where he was put in jail. He had to sleep on a damp gravel floor. When arrested he didn't even have a chance to tell his family where he was being taken.

While Peter was in prison, Mary Ellen's fourth child, Martha Jane, who went by Mattie, was born on August 28, 1887. Then one Friday night in September, Eliza Ann, who had always been in poor health, had been ironing sheets when she suddenly became very ill. Early in the morning of the following Sunday, she died at the age of thirty six on September 25, 1887. The family was grief stricken. Forty eight wagons accompanied her remains to the cemetery with a white top buggy serving as the hearse and another one for the immediate family to ride in.

After spending the next several months in prison in Salt Lake, Peter was granted pardon by President Grover Cleveland now that he only had one wife and was released in April or May of the following year.

With

the loss of her sister, Mary Ellen raised Eliza Ann's three children

ages eleven, eight, and five as if they were her own. Many people in

Clarkston couldn't tell which children were which as Mary Ellen

showed very little preference, if any.

His keen sense of humor and his many practical jokes was appreciated and

remembered by many residents of Cache Valley. He loved to write and became

a correspondent for the Logan Journal Newspaper and reported on the news

of Clarkston and provided human interest stories for forty nine years. His

wit and antidotes were published with the pen name, “Sanko”.

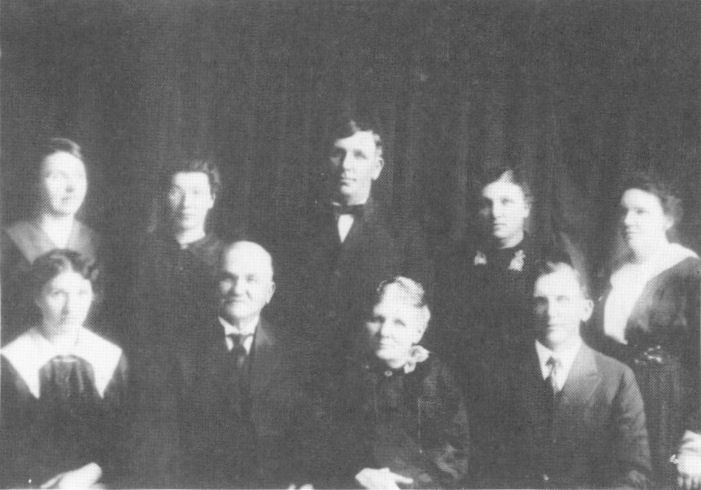

The Barson Family in 1896. Back row; Ellen, Bird, Hyrum, Liza, and Vie. Center: William,

Mary Ellen, Peter S. Barson, a portrait of Eliza Ann. Front: Mattie and Bessie.

|

Peter's family was compete with the birth of Mary Ellen's last child, Bessie

Cloe, who was born on May 29, 1890. By this time the older children

were getting older. On June 10, 1897 Liza married Joseph Maurice

Godfrey. Then six months later Hyrum married Effie Bell on December

22nd. And the following spring, Nell married Thomas Henry Godfrey on

March 23, 1898. On the heals of the weddings came the arrival of

grandchildren the first being Liza's daughter, Mary Eliza Godfrey,

who arrived on April 13, 1898.

| |

The home built in 1899. Peter and Mary Ellen are standing on the porch. Notice the

young woman in the ruffle skirt sitting on the rail. Another young woman is sitting on

the steps with a small cild. Three children are in carriage and two more on the horse.

|

In 1899 a new red brick house was built next to the two story frame

house. He had established a beautiful grove of trees known as "The

Timber Culture," or "Barson's Grove." To any child and

most grown-ups, this was an enchanted spot in a big, busy world.

There

were no road signs leading to it. It was free and bewitching, and the

"welcome" sign was always out. One almost felt there were

unwritten welcome notes posted here and there on the trees that read:

"The time to be happy is now. The place to be happy is here. The

way to be happy is to make others happy." So-o-o, if trees could

only talk, what interesting stories could be told.

At

any unexpected time, the members of the Barson family would receive

this kind of a notice: "Hey, folks, it's party time again."

It could mean a picnic, a family reunion, birthday party, a hurriedly

prepared social in honor of relatives from Missouri, or maybe just a

peaceful quiet afternoon at the grove in the cool shade for the women

folk and children.

Every

Barson gathering included the kissing ceremony that always took place

going and coming. Peter demanded that everyone but his sons-in-law

line up in a row and kiss him. The kisses were his own way of saying,

"I love you."

Many

times during the summer season one would see many horse-drawn wagons

wending their way up the dusty lane to the grove. These wagons were

filled with men, women, and children, anxiously anticipating another

fun day at the timber culture.

Mattie, Mary Eliza Godfrey,and Bessie

about 1900 | |

When all had assembled, and the teams were tied a safe distance from the

picnic area, the fun began. The happy group both young and old were

cordially and warmly welcomed; yet, cautioned to all mind their

manners. Namely, the family rule (always clean up your plate). Seems

Peter always wanted his grandchildren to become durable grown-ups

and believed this training should start early.

The

warm noonday sun and soft breeze brought the tantalizing odor of well

cooked vegetables, roast beef, tempting salads, and fresh baked pies,

cakes, and rolls. Old fashioned lemonade as a tangy thirst quencher

was enjoyed by all – even though the chill had been taken off by

the long wagon ride in the sun.

Oh,

for the preparation of these socials. The women had gone to endless

bother to make these events a big celebration. The food was prepared

by all the women who came and only sickness kept any family away.

The

children were everywhere and into everything, their squealing and

laughter shooting up all over like little rockets.

At

last the call "Dinner is being served!” saved the day.

Hungry-eyed children were served first. One can imagine how many good

laughs are in store when guests from twenty one days to eighty years

go on a picnic together. Somehow amid the laughter and talking and

occasional crying of the babies the lovely picnic dinner was over.

After

that, the men sat around and talked big about the moneyed boys in

Wall Street. They talked politics. They almost forgot their own

troubles because everyone was in the same boat.

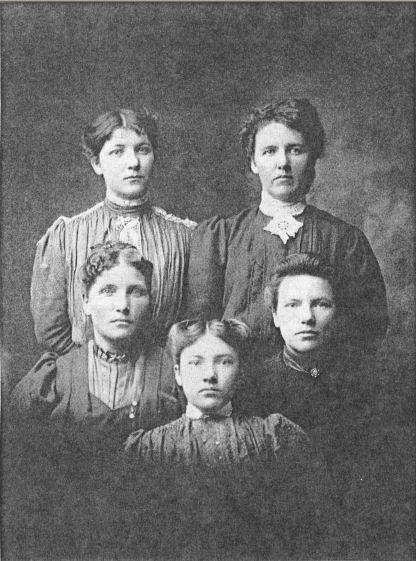

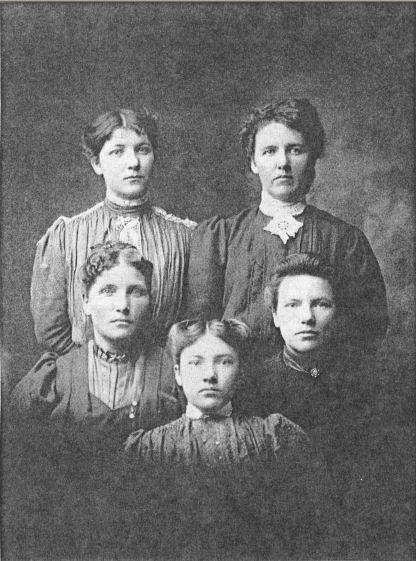

| |

The Barson girls; Back: Mattie and Vie, Center: Liza and

Nell, Front: Bessie

|

The children played “Drop the Handkerchief," "Blind Man's

Bluff," and "Hide and Seek,” while others enjoyed the

newly installed rope swings.

The women cleared away the dishes and talked about a new gelatin fruit

salad one of the nieces home from college had introduced that day.

Every woman was burning with envy wondering how to get the

recipe.

The afternoon wore on and the children had about played themselves out

and were wearily dropping on the quilts and grass to rest when one of

the aunts called, “Ice cream - come and get it.” There was a

noisy scramble for places, a little pushing and a few cross words.

It

seems homemade ice cream and cake has always been the most delicious

party refreshment. Each family with an ice cream freezer had made a

gallon or two so there would be plenty. The men brought ice from town

as most everyone's ice houses had been sawdust bins for weeks.

After

the refreshments had been enjoyed, a short spicy program was given.

There

were recitations and short pieces by the younger people, a few

off-key songs by the school children, stories or funny jokes by the

adults. Then Grandma's favorite songs were sung -- she especially

liked "In The Good Old Summertime," and "Red Wing.”

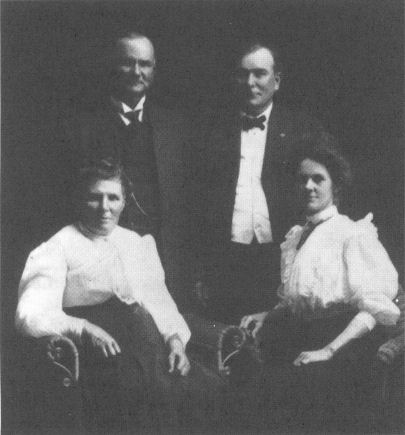

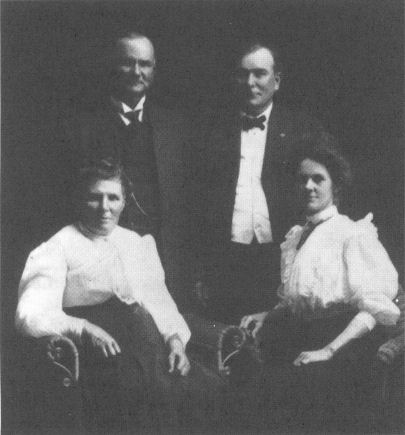

Peter and Mary Ellen with John and Frances - 1910 | |

As the final clearing up of the picnic grounds was in process, one

father said to his wife in a relaxed tone, "This surely was a

good party." His wife tactfully replied, "It's another of

those good old Barson get-togethers, and the children certainly

enjoyed it.”

Oh,

for the dozens and dozens of family parties held in that grove. If an

unanticipated grumbling thunderstorm unexpectedly made its

appearance, those assembled quickly loaded lunch boxes, table cloths,

quilts, and families into the wagons and dashed the two blocks to the

Barson home. Here everyone was welcome and there was always room for

all, and the program was continued. This time with the aid of musical

instruments and gifted musicians.

In

later years when Peter retired, he and Mary Ellen moved back into

Clarkston and Hyrum and Effie lived on the farm.

Three

more weddings took place during the first decade of the new century.

On January 7, 1904 Bird married Anna Elizabeth Rasmussen. On February

27, 1906 Vie married Willard Richard Dahle. And on December 5, 1906

Mattie married Thomas Arthur Goody.

For

many years Peter served as justice of the peace. On April 23, 1912 he

performed the marriage of his last daughter, Bessie, to Phillip Hyrum

Rasmussen.

| |

A picture post card to Mary Eliza Godfrey from Oronogo, Missouri dated 2 PM

May 18, 1910 from Peter and Grandma Barson and Bessie. He wrote "Kind

regards to all who look at this photo." Peter is sitting on the running board. |

The years passed by, and then one day a surprise letter came to Peter from a Clarkston missionary who was laboring in Missouri. He noticed the unusual name of Barson on a doctor's shingle as he was proselyting, and his curiosity was aroused. He called on the doctor and asked him if he knew Peter Barson of Clarkston. The doctor said he once had a half-brother named Peter, but hadn't seen him since he was a small boy. He wrote at once to Peter and confirmed the fact that they were brothers.

How happy he was when on May 17, 1910 he and Mary Ellen, and Bessie left

by train for Oronogo, Missouri to see his long lost brother. At last he found

someone who was related to him. As the brothers met, the scene was most touching.

They threw their arms around each other and wept for joy. Both had found a

brother in a world that held them apart.

Another picture post card

addressed to Mrs. Mary Godfrey

Buttars from Oronogo, Missouri

dated June 3, 1916. He wrote:

"Getting ready to go west soon.

We will make our home in Zion

soon." Signed Grandpa and

Grandma Barson.

Standing: John Barson, Mary

Ellen and Peter. John's wife

Frances is seated with an

undentified child. |

|

|

|

John, his wife, Francis, and three daughters made several trips to Clarkston

where family ties were strengthened. We kept in touch with letters, and gifts

although our differences in religion were never mentioned. On one of Uncle

John's trips to Utah, he and Peter found their father's grave in a Salt

Lake cemetery and erected a monument to him. They had their picture taken

by the monument as if to say, "Yes, father, we have found each other."

On another visit to Clarkston, Liza's husband was gravely ill. John did

all he could to save Joe. One morning his condition seemed so much better that Dr. Barson

decided to climb the mountains west of town to the top of Gunsight.

When he returned later in the day, Joe had died on May 24, 1912. John

and Fanny were very impressed with the beautiful way the Mormons laid

their loved ones to rest in their white temple robes. They thought

the services were impressive and comforting.

In addition to being the justice of the peace, Peter also served as a

school trustee. His interest in the public schools was outstanding.

He made more visits to the school than any any one else. He related

on numerous occasions to the students how he had driven oxen, mules,

horses, and automobiles.

The term "an apt Englishman" describes Peter S. Barson. He has tried almost every trade imaginable. He labored as: chore boy, cowboy, army cook, shoemaker, musician, well digger, farmer, newspaper correspondent, printer's assistant, auctioneer, school trustee, Justice of the Peace, politician, county health officer, and town butcher, He has driven oxen, mules, horses, cows, owned two automobiles, and pushed wheelbarrows for hundreds of miles. He helped to build dugouts, adobe, mud, willow, frame, and brick houses.

Peter was a good provider and enjoyed lots of company regardless of how much work it made the women of the household. He entertained everyone in Clarkston besides every peddler and politician that happened to come to town and when he said it was time to go home, they went whether they had their visit out or not.

His guest list includes three L.D.S. church presidents, seven apostles, four U.S. senators, four governors of Utah and one from Colorado, fourteen state legislators, and all of the local Democrat nominees from 1898 to 1912 and hundreds of others ranging from Chief Waskakie to Amos Cromwell from the East.

His library included scrapbooks of important current events and signatures of the Prophet Joseph Smith, Grover Cleveland, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and Theodore Roosevelt. He also gathered everything published to further the cause of the Democrats, and being a lover of music, the old organ displayed the latest copies of sheet music, a luxury in our town.

The Barson Family.

Back row: Vie, Mattie, Hyrum, Liza, and Nell. Front row: Bessie,Peter, Mary Ellen, and Bird.

|

No history of Peter would be complete without a few of his practical jokes. A Man once teased him about his bald head, and he replied. "I had my choice, brains or a bald head. How come you choose the latter?"

He often said to his guests, "Now don't go away like you did last time and say you didn't get enough to eat."

The guests would look embarrassed and reply, "Oh Brother Barson, I didn't say that."

Then he would say, "It must have been someone else."

On his train trip to Missouri, he was always making someone laugh by having the passengers look out of the window at something that wasn't there such as watermelons on the desert. One passenger said, "It breaks the monotony of the trip to have a jolly-joker like you along, but what would happen if we believed all you said?"

Peter answered, "You'd find that a bit of nonsense makes the world a happier place. When things look the darkest, I try to smile. If, I've done wrong, forgive me."

"You are one in a million," a voice shouted from the back of the car.

He always said the sadness in his own life made him want to bring joy to others.

He

met his appointments promptly and advocated keeping out of debt.

Music, interior and exterior painting, culture of flowers, and the

making of scrap books were among his hobbies. He played the violin,

enjoyed baseball games, picture shows, and dancing, and visits from

his friends. He was a financier and was respected in the community as

having keen sense in making and keeping the good old American dollar.

He was ambitious, moved fast, and always grunted while he worked. Those

around him were expected to keep the same speed whether it was

feeding the pigs or playing a game of cards. It was always "get

a move on.” He punctuated his sentences freely with hell and damn,

and if the occasion required more emphasis, he could call into use

stronger adjectives.

He

lived by his own code of religious ethics. If he saw someone in need,

he donated then and there, never caring whether his kind deed got

recorded in the good books or not. Peter had no "Word of Wisdom”

problems in his opinion. He was an Englishman and liked his tea,

therefore he drank it. He would also drink a cup of coffee if he

thought sociability required it.

| |

The Barson home in Clarkston

|

He went to church, but when he felt like it he stayed home and was not

bothered by a gnawing conscience for having done so. On one occasion

he was found guilty of working on the sabbath. In his defense he

plead that “the ox was in the mire.” After being chastised, he

asked for forgiveness with a twinkle in his eye that said that he

would do it again if he thought it was necessary.

The

rules of convention gave him no concern. If he wanted to laugh loud

in church he cut loose, and if the speaker was dry or lengthy, he

would get out his big gold watch and snap the lid open and closed in

the most annoying manner. Sometimes he juggled and dripped his uppers

to the amusement of the kids and the embarrassment of his relatives.

Underneath this rough exterior, he was a very prayerful man. Thanking the Lord

for his food and asking Him to bless it was an obsession with him. He

once said, "Never be too damned lazy to thank the Lord for your

food. If you had been as hungry in your life as I've been in mine,

you'd never forget the giver of your food.

His family was always important to him. As his grandchildren grew up and

had children of their own, they were just as precious to him. Being

a story teller, he loved an audience. At family gatherings he would

entertain his great grandchildren. He gave them each a nickel to sit

around him on the floor while be played his violin and told stories

of fighting Indians and riding for the pony express. He had a

phonograph player that had a little man that dances around the record

as it played. If one of the kids got up to leave before he was done,

he took their nickel away from them.

Peter was left a widower with the death of Mary Ellen on December

11, 1935. He lived seven more years. In his later years, he always

wore his black homemade alpaca coat, his tie tied in a square knot,

and his gold-headed cane under his arm. He always smelled of bergamot

and peppermint candy, and invariably whistled that same old tune.

Age was upon him and he knew that soon he would be meeting someone

in the sweet bye and bye. He loved that song, "We Shall Meet in the

Sweet Bye and Bye." He sang it, played it by ear on the organ, and

sawed it, with many sharps and flats, on his old fiddle.

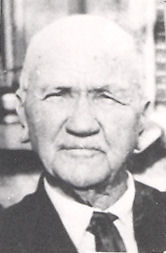

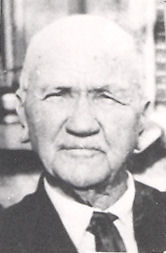

Peter S. Barson | |

The human desire for longevity prompted Peter to try every herb,

laxative, tonic, or cure-all ever advertized, and he took his "medsen"

without fail. It might have helped him, at least it didn't hurt him,

for he lived to be ninety-three years old.

And then the end came on November 12, 1942. Everything was quiet in

old family home that would soon be no more. There sat the empty black

rocking chair, his hat was on the rack, and his cane stood in the corner,

all seeming to say, "Never Again." The family sat and talked in soft,

solemn tones of the joys of the past, and what a good father he had

been – though the demanding patriarch he was.

He lay in state in his own parlor. There was the carpet, with the big

red roses, he had chosen and the walls covered by enlarged pictures

that he had hung, and everything was saturated with the sickening smell

of carnations and wilted roses. The old clock chimed the solemn hour

of twelve. Time came for the funeral. Then the cortege left for the

chapel, and family members entered according to age.

The solitude and mystery of death prevailed. The organist played, "Nearer

My God to Thee" as the bereaved were seated amid appropriate nose-blowing

and sniffling. The choir sang "Shall We Meet Beyond the River?" Then a

prayer was offered, followed by remarks and eulogies, but his passing

might have been best expressed in his own words. "And now the curtain

goes down. It has been a beautiful day." Yours truly, Sanko."

The

main sources of this story are Sanko: The Life Story of Peter Sheffield

Barson and other writings by Ann Godfrey Hansen and The Life Story of

Mary Eliza Barson by LaRee Barson McCauley.

|