Samuel Barson

15 July 1825 – 25 August 1865

There was once a young shoemaker in Wellingbourough, Northamptonshire,

England by the name of Samuel Barson. Samuel was born in

Wellingbourough on July 15, 1825. He was the third child of Samuel

Barson Sr. and Jane Rixon of Wellingbourough.

Samuel Barson - 1861

At the age of eighteen he joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, being baptized on April 12, 1844. In his association with other members of the Church he became acquainted with another young convert from Wellingbourough, a dressmaker by the name of Ellen Sheffield. Ellen, the daughter of Peter Sheffield and Charlotte Munden, was born on June 26, 1826 in Wellingbourough. In time, they were married on December 26, 1846 and made their home in Wellingbourough.

Their first child, Orson Pratt was born on October 15, 1847. Peter was born on February 12, 1849 in Wellingbourough. Sadly, Orson died four months after Peter was born. John was born in 1850, Sarah Ellen on February 18, 1851, and Mary Ann on February 9, 1852. Sarah died on June 3, 1852.

Being a Mormon in England during those days was not a very popular thing to be. Persecution was very severe and Samuel and Ellen longed to immigrate to Utah and unite themselves with the main body of the Church. They worked and saved everything they could to prepare for the long journey.

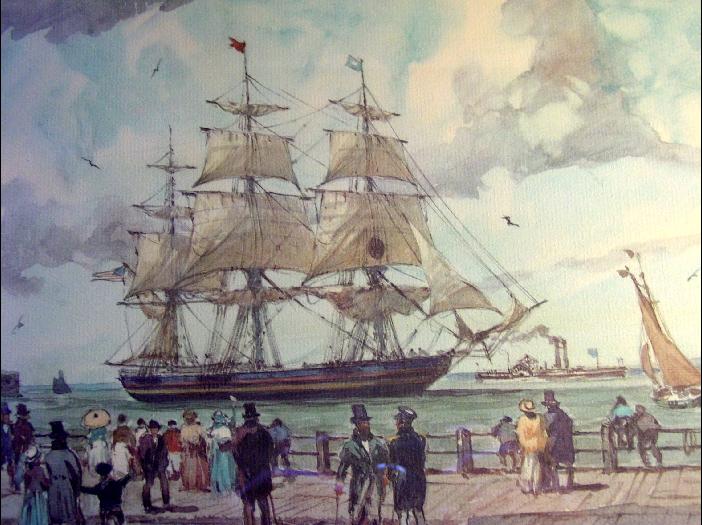

As

England disappeared in the distance the sweet singing ceased and many

began to feel seasick. All that night the wind howled fiercely; the

sea was rough; the ship was driven from its course. The next morning

the sea was still rough and the wind was blowing. During this day the

Windermere sailed by the remains of a wrecked vessel. Masts, sails

and other fragments were floating around. Likely, a few hours

previous many despairing souls had tenaciously clung to these same

objects for relief that never came. All had been consigned to a

watery grave for no signs of life remained and the rolling waves

swept over the bodies while the wind howled its tribute for the dead.

Life

on the Windermere was growing monotonous for its accommodations were

inadequate for so many passengers. Some began to recover from

seasickness, but many were still ill and some were confined to their

berths.

On

the 12th day of March, at about seven or eight o'clock in the

morning, an exceedingly fierce storm arose. The masts cracked and the

sails were torn in pieces. The captain of the Windermere expressed

fears that the ship could not stand so heavy a sea, and in speaking

with Daniel Garn, the president of the Saints on board, said, "I

am afraid the ship cannot stand this storm, Mr. Garn, if there be a

God, as your people say there is, you had better talk to Him if He

will hear you. I have done all that I can for the ship and I am

afraid with all that can be done she will go down."

Elder

Garn went to the Elders, who presided over the nine wards in the

ship, and requested them to get all the saints on board and to fast,

and call a prayer meeting to be held in each ward at 10 a.m. and pray

that they might be delivered from the danger. The waves were lashed

with white foam, the storm continued in all its fury, but precisely

at 10 a.m. the prayer meeting commenced and such a prayer meeting few

have ever seen.

The

wind roared like a hurricane. Sail after sail was torn to shreds and

lost. The waves were very large and as far as the eye could see,

seemed to be one angry mass of rolling white foam. The hatches were

fastened down. This awful storm lasted about eighteen hours, then

abated a little, but it was stormy from the 8th of March until the

18th. On

the 14th of March, which was two days after this terrible storm,

smallpox broke out. Forty in all, came down with it. Three days later

the ship caught fire in the galley. At this time they had not seen

land for three weeks; when the cry of "Fire! The ship is on

fire," rang throughout the vessel, wild excitement and

consternation prevailed everywhere. The sailors plied water freely,

all the water buckets on board were brought into use and soon the

fire was under control.

As the smallpox epidemic spread, ten people died from it. The funeral

services were very impressive; a funeral at sea is the most

melancholy and solemn scene perhaps ever witnessed, especially when

the sea is calm. A stillness like that of death prevailed with us

while an old sailor, at intervals, would imitate the doleful tolling

of the bell of some old church, such as heard in some parts of

England. Funerals were becoming frequent. About

the time the Windermere was six weeks out of Liverpool the passengers

had not seen land from the time they had entered the Atlantic. The

days were generally mild and the weather very pleasant. The sun set

and the bright, pale moon seemed to be directly overhead. On the 8th

day of April they came in sight of the Island of Cuba.

After

facing a terrible storm, a smallpox epidemic, and a fire aboard the

ship, another fearful calamity threatened them. The sea and wind

became very still. Without wind, the ship had no means of propulsion,

only to drift with the current. The fresh water supply was getting

short, and the store of provisions was falling. The passengers were

limited to one hard, small biscuit for a day’s rations.

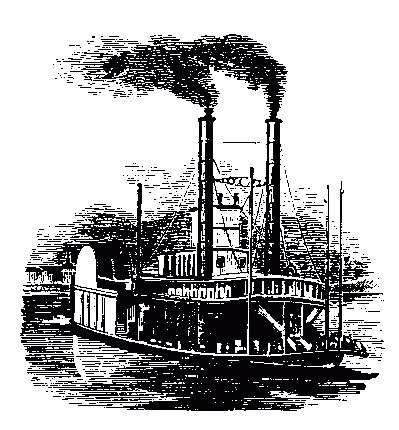

On

the morning of the 20th of April the ship entered the mouth of the

Mississippi River. The passengers were glad to look upon the

plantations along the banks of the river than the great strong

surging waves of the Atlantic which they had been through. The

Windermere arrived at New Orleans 23 April, 1954. Samuel, Ellen,

Peter, John, and Mary Ann had survived the perilous voyage, but there

was still a long ways to go.

With saddened

hearts, the father and his three little children journeyed on to St.

Louis, where Ellen's father, Peter Sheffield lived. He had immigrated

to the United States sometime earlier to establish a large tannery.

He persuaded Samuel to leave his two smallest children, John and

Sarah, with him now that their mother was taken. Samuel consented,

with the understanding that he would send for them later. At that, he

soon continued on with Peter. From St Louis, the two of them traveled

up the Missouri River on another steamboat to Westport, Missouri near

Independence to the staging areas for wagon trains bound for Salt

Lake City.

As

they approached Fort Kearney, they began to see signs of buffalo. The

Bison were strange looking animals. The herds extended for miles in

length and breadth and the plains appeared black with them.

For three days, Chimney Rock

could be seen in the distance as they approached the prominent land

mark. On the third night the camped alongside it. When about six

miles east from Fort Laramie, they came to a very large camp of Sioux

Indians and passed by them unmolested. A few days later, word came

that the Indians had killed a couple of soldiers. The company and the

one following behind along with a few straggles on the Oregon Trail

joined together temporarily for protection . The Indians did not raid

the wagon train but did attack Fort Laramie, killing several

soldiers.

Finally,

on the last day of September the Richardson Company arrived in Salt

Lake City. It had been a long journey for Peter and his father, one

fraught with peril and loss. They had not been in Utah long when

their hearts were saddened with the news that the John and Mary Ann who

had been left in St. Louis had died.

Samuel

and Peter made a new home for themselves all alone in a new land.

After arriving in Salt Lake City they lived with Bishop Tingey until

Samuel found work. Samuel Barson was a shoemaker and soon as given

employment with the Jennings Company. Samuel married Sarah Ann

Jennings on October 25, 1855 and home life was established again.

Ann, was a twenty two year old convert from Yorkshire England.

Samuel was sealed to both Ellen (by proxy) and Ann on March 14, 1856

in the Endowment House.

Their first child, who they named Samuel, was born and died on

January 9, 1858. Samuel,

still being poor, made the tiny coffin and carried it on his

shoulders to the cemetery. During

the winter of 1857-58 the Saints were ordered to leave Salt Lake City

and move south because of the coming of Johntson's Army. Accordingly,

Brigham Young directed all of the people north of Utah County to

leave their homes and proceed southward, Thus began the "move".

During the spring of 1858 thirty thousand people migrated southward.

When the crisis was passed they were able to return to their homes. Soon

after Samuel Barson was blessed with more means and he bought a lot

and a one room adobe house. Two more children were born to Samuel and

Ann: Martha Jane on March 15, 1860 and John William on December 15,

1862.

Not

long after that, Ann sold their home, remarried, and and left the

territory, and the Church. and she took Martha and John with her and

moved to Cherokee County, Kansas near Joplin, Missouri. Martha died

at age thirteen, but John went on to become a doctor. The day they

left, Ann had handed Peter fifty cents, climbed in the stagecoach,

and left him to face life on his own.

Peter

kept worrying about Mormonism and wondering if it were true. He

wished that he could ask his father. One night as he was lying on a

lounge thinking and pondering over religion, a light appeared in one

corner of the room. In the light he saw his father clothed in temple

robes. This was his chance, so he asked his father if Mormonism were

true. Samuel answered, "Yes, but not the way some people live

it.” Peter had said, "If all the world would go in darkness

and people say there was no resurrection, I would believe in

Mormonism and the resurrection, because I have seen my father."

The

main sources of this story are The Life Story of Peter Sheffield

Barson by Ann Godfrey Hansen. The voyage of the Windermere is from

the British Mission records of 1854 by Evelyn A. Sessions found on

the Craner Family website, www.craner.org. The part about crossing

the plains is from Reminiscence by James Moyle published in 1886

taken from /www.lds.org/churchhistory. Also from A history of the

Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

With hearts full of faith, they embarked on what would prove to be a long

and arduous journey. On Wednesday, February 22, 1854, the ship

Windermere sailed from Liverpool with 460 passengers, all Latter-day

Saints; including Samuel age twenty eight; Ellen age twenty seven,

Peter age five, John age four, and Mary Ann age two. As the vessel

started in motion, the songs of Zion, blending in soul-inspiring

harmony, thrilled the souls of the passengers and their many friends

and families standing on the shore gazing at the departed vessel,

shouting farewell, goodbye with eyes streaming with tears.

The ship rolled from side to side. The large boxes which were tied with

ropes under the berths broke loose with pots, pans and kettles and

rolled with terrible force on each side of the vessel. Although the

prayers were fervent and earnest, as the pleadings of poor souls

brought face to face with danger and death, they ceased their prayers

to watch and dodge the untied boxes, and great confusion prevailed

for some time.

The Captain sent some sailors in a small boat to intercept a ship that

was passing in the hopes of getting more provisions, but they failed.

The Windermere now passed the western points of the Island of Cuba.

The passengers had a good view of the lighthouse located on the most

western point. The Gulf of Mexico was before them. But at the end of

five weeks favorable winds set in and the ship made 1,000 miles in

four days.

After a few days in New Orleans, the Barson family continued

their journey and traveled up the Mississippi River by steamboat.

While sailing up the river, cholera broke out. Ellen Sheffield Barson

was stricken with the disease and died on May 15, 1854 at the age of

twenty seven. At the next stopping place, her body was taken ashore

and she was buried on the banks of the Mississippi River.

At Westport, they joined the company of Captain Darwin Richardson. On

June 17th the company moved out with about three hundred people and

forty wagons. Samuel and Peter walked across the plains to their new

home. Enroute they encountered large herds of bison and the various

tribes of Plains Indians.

The Pawnee Indians would come and demand gifts for traveling through

their country. After leaving them behind, they came into the country

of the Cheyenne Indians. The Cheyenne were more aggressive and were

constantly harassing the wagon trains passing through. The were

particularly after cattle and trying to run them off.

Samuel Barson was a musician and a member of the Tabernacle Choir. The

history of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir coincides with the

establishment and progress of the Mormon settlements in the Great

Basin region beginning in 1847. A choir was officially formed in

August, one month after the pioneers entered the valley and performed

during the first general conference of the Church in the Salt Lake

Valley on August 22. The first, or "Old" Tabernacle

located on Temple Square was completed in 1851. A small organ

handcrafted in Australia was brought to Utah in 1857. While on his

way to choir practice, Samuel caught a severe cold. Pneumonia

developed and resulted in his death on

August 25, 1865.