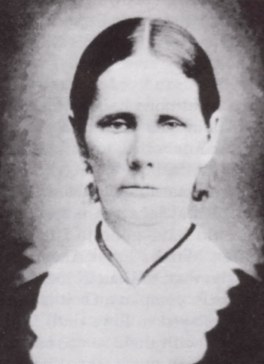

Mary Angeline Frost

16 March 1836 - 18 March 1919

Mary

Angeline Frost, oldest daughter and first child of Samuel Buchanan

and Rebecca Foreman Frost, was the mother of Mary Frances Adams,

second wife of Charles William Merrell. Mary, as Mary Angeline was

called, was born 16 March 1836 in Hancock County, Illinois.

Mary told her children in later years her first recollections as a child. Her father’s family lived in or very near Nauvoo, Illinois, and she recalled sitting on Joseph Smith’s lap or walking around the yard holding onto his hand. She said the Prophet sometimes visited her parents and borrowed their baby to take home to his wife to comfort her after she had lost an infant. Mary remembered all her life the moans and cries of Joseph’s followers when his body and that of his brother Hyrum were brought from Carthage where they were killed in 1844.

Though Mary was raised in a household of plenty, she learned to be conservative with material possessions, a habit which was advantageous to her in later life. When she was very young she cooked for her father’s hired hands and cared for her mother during her confinement after giving birth to Mary’s siblings.

On 29 January 1854 Mary was married to Jerome Jefferson Adams in Fremont County, Iowa, where they remained until after their first four children were born. They were: Rebecca Jane, born 2 October 1854; John Quincy, born 22 March 1856 in Sidney, Fremont County; Cora, born 27 December 1857 in Sidney; and William, born 6 September 1859 in Sidney. It is believed that the Adams family went west in the same company of pioneers with whom Mary’s father and siblings traveled; but apparently her husband was not a member of the church in which her father was active. Mary and Jerome intended to go on to California.

During the winter spent in the Salt Lake Valley area while trying to recover the financial stability that would permit them to continue westward, Mary’s husband worked for the Mormons. He became converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and lost his desire to go to California. He later gave his baptism date as December 1861 (Colonia Diaz Ward Records). While living in Cedar Valley, Utah County, Utah, Mary gave birth to her fifth child Martha on 27 September 1861.

In late 1861 or early 1862, Brigham Young sent the Adams family to Cache Valley to help settle that area. This is the long, fertile valley running northward from Avon (several miles south of Hyrum) on the south, continuing into southern Idaho. It received its name from early trappers who would cache their furs in the area while they went on further trapping expeditions. Mary’s sixth child and fourth daughter Mary Frances was born on 27 August 1863 in Richmond, Cache, Utah.

The family endured many hardships in that location, partly due to their poverty, but also because of the cold climate. Bedding was scarce, so during the winter Mary put her children in the foot of her bed to keep them warm at night. At one time they had nothing to eat for six weeks except boiled potatoes, and during one winter a brood sow and her litter of pigs were kept in one corner of the house to keep them from freezing.

In December 1865 Mary and her husband started on a trip to Salt Lake City in answer to a call from their church leaders. When they reached Bear River on December 8, Mary gave birth to her seventh child, Jerome, Jr., so they turned around and returned home. When they arrived there, her bedding was frozen to the wagon.

In 1867 Jerome and Mary were called by Brigham Young to go to Nevada to help settle the place then called “Muddy Mission.” As they headed south in their wagons it must have been another very difficult trip for Mary. They went by way of Spring City, Sanpete County, where her parents lived, arriving there on the evening of 24 October 1867. At ten o’clock that night Mary gave birth to their eighth child, Sarah Louisa.

After ten days the Adams family continued their move to a place that was very different from lush, green Cache Valley in which they had lived for the previous few years. The Nevada settlement was dry and dusty, extremely hot in the summer, windy, isolated from surrounding settlements, and infested with insects, snakes, and other animal life that combined with other elements to make their life nearly unbearable. While living in St. Thomas, another son, Foreman Eastwood, was born on 10 January 1870.

Soon after Mary’s husband left in 1870 to sell grapes and find some means of earning money, the settlement was disbanded and Mary and the children were moved by kind neighbors to Washington City, Washington, Utah. In that location John Quincy, fourteen years of age, found work in the cotton factory and Mary worked at whatever she could do to earn food to sustain the family. She received half of the milk from a neighbor’s cow in exchange for doing the milking. Each day she would take a bottle of milk and a stack of hotcakes to the factory for John Quincy’s lunch.

After her father heard of Mary’s situation he sent Redick Allred and his son to move the Adams family to Spring City where the Frosts lived. Mary again worked to provide for her children until her husband returned from “seeking his fortune.”

The family remained in Spring City for four or five years, during which time two more children augmented their family Hettie Millicent was born on 23 November 1872, and Georgiana “Georgia” was born 19 March 1874.

In 1876 they were called to go to the settlements being established on the Little Colorado River in northern Arizona. During that trip, their wagons were loaded so heavily that the family members were obliged to walk. Mary’s daughters (Richardson & Tenney) wrote about the experience, “I remember my mother walking many miles day after day in the rain and shine. Once we traveled all day in the snow until after dark, though my father seldom traveled after sundown. We camped at one of Little’s ranches. When we awakened in the morning the snow was so deep it covered the hubs of our wagon wheels.

“It was quite a little way to the ranch house, but someone had broken a sort of trail with the horses. When we got to the house they had a fire and Mother was cooking breakfast. They had the horses in one side of the house. The smell of the horses and the warm fire caused my sister Fan to faint.

“[Later] Pa and John took one of the wagons and Mother and some of the children, leaving three of us at the ranch with the other wagon that was left. We were very hungry. My brother went to the wagon . . . and found a small head of cabbage and a handful of dried peaches. We traveled until late that night to get to the other wagon. Before we got there we could see a little flickering light and when we reached it our little mother was sitting over the fire in the snow frying hotcakes for her hungry children.”

On another day Mary walked in advance of the wagon and was two miles ahead of the vehicle. When night came, she knew her husband would have stopped to make camp, so she walked back to the wagon to feed her nursing baby with her clothes frozen to her knees. In the meantime Jerome had made camp, built a fire, and prepared supper for the children. Sadie told of him handing her a dish of “molasses and mush,” which was the only thing they had to feed the baby until Mary could get back and nurse her. During that long trip and other migrations by wagon, Mary made the best use of the time when they stopped at watering places. She washed their clothes, bathed the children, and braided the girls’ hair in what they called a “night cap,” later called a French Plait.

When the family arrived at Ballinger’s Camp (later named Brigham City) on the Little Colorado River, Mary was “set apart” as a nurse and midwife. When she cared for a woman who had given birth, her duties included not only delivering the baby but taking the patient’s laundry home to wash and iron, cooking for the family (if she had other children) and caring for the mother during the confinement, a duration of several days.

Her early training in frugal living paid off when flour was rationed until the colony could finish constructing a grist mill. While her neighbors spent much of the night grinding wheat with a small mill or substituted boiled wheat in their diet in place of bread, Mary never ran short of flour, due to her conservative practices of long standing.

For the first two or three years in Brigham City, Mary made cheese for the neighbors as well as for her family. They brought small amounts of milk and she kept a record of the quantity brought by each one, then apportioned the finished cheese according to the amount of milk contributed.

Mary went with her husband to spend the summer of 1879 in the mountains taking charge of the dairy run by the members of the United Order (Lake) in which they participated. A daughter later told about their trip to the dairy, which necessitated camping overnight on the way. One of their daughters, Mary Frances Merrell, was living at the sawmill in the same location as the dairy, and the Adamses were going to stay with her for the summer. When it got dark and they had to make camp, they had not caught up with the mother, who had taken the baby and walked ahead of the wagon. Jerome cleared a circle of brush, built a fire to warm the ground, and made beds for the children in the soft warm dirt. The children were very much afraid of what might have happened to their mother and begged their father to drive on until they found her. He said nothing, but kept working to get their beds ready, and they stayed there overnight. The following morning the children watched on each side of the road for signs of their mother and baby brother having been eaten by some wild animal. They reached the mill and learned that she had kept walking until she reached their daughter’s place at midnight. The children were overjoyed, but hid their feelings, as it was the practice of the family to make no outward expression of their deepest emotions.

After spending the summer at the dairy, the Adams family returned to their home at Brigham City, where Mary was energetically involved in community and church activities. She taught Sunday School, and when that organization wanted to give special cards of merit, she sketched pictures on the cards, colored them with different shades of dye, and made patterns from cloth to make borders on the cards.

There were other examples of Mary’s ingenuity. During their first year in the Arizona colony, the family members were short of clothing. Mary used a tent and a wagon cover to make clothes for her husband and sons. She washed them until the fabric was beautifully white and kept them that way. From the same material she also made shoes for her children, though they lasted for only a week. When the soles wore out, she replaced that part of the shoes with more of the same fabric.

The same qualities of resourcefulness that Mary exhibited in the Arizona Mission were valuable to the Adams family after their move to Mexico. Mary practiced as a midwife in Colonia Diaz, and continued to raise her large family without complaint. Her husband passed away in 1902, leaving her alone to endure the troubled years preceding and during the Exodus.

When in late July 1912 the revolutionary army carried out a savage raid on the colony she had called home for 23 years, Mary was left homeless. She probably made the trek from Diaz, along with the other expatriates, to live in the tent city established in Hachita, New Mexico.

In early 1913 she was staying at Corner Ranch, home of her son-in-law Charles Edmund Richardson and one of his wives, Rebecca. Later on Mary stayed with others of her children, including Fannie Merrell, with whom she was living in 1915. Mary died on 18 March 1919 at age 83 at the home of her daughter Sadie (Sarah) Richardson in Thatcher, Arizona.

Mary’s daughters later recalled some of her character traits. She was fastidious in her dress and personal cleanliness throughout her life. Her daughter Sarah wrote that when she, the eighth child, was fifteen years of age her mother was often thought to be her sister. Mary had good health and enjoyed life to its fullest regardless of their economic circumstances. She was a strict disciplinarian regarding her children, but she was fair in her dealings with them whenever there was a misunderstanding or an infraction of the rules that prevailed in their family life.

If Mary could have been considered overzealous in doing her household tasks, it might have been in the laundry area that she went to the extreme. Her children wrote that on wash day she felt ashamed to hang out a small washing, so she searched through the house and got items that really did not need washing in order to have her clotheslines full. If there was mud underneath her lines, she hung out the clothes in her bare feet to avoid getting her shoes muddy. Her attitude toward hard work was that there was a certain amount of work to do and she proceeded to do it in the most rapid and painstaking manner with no complaints. Considering the disparity between the circumstances of her early years and the many hardships she endured during the extended migrations with her husband and large family, it is no wonder that Mary Angeline Frost Adams is revered by a large progeny who benefit from her legacy of stamina and sacrifice.

7 February 1835 – 5 May 1902

Jerome Jefferson Adams, son of William J. and Jane Eastwood Adams, was born 7 February 1835 or 1836, in Columbus, Franklin, Ohio. He ran away from his relatives when he was between the ages of twelve and fourteen and started a life of autonomy. He always said his relatives were good to him, but he simply didn’t want to be dependent on them.

As a teenager he worked at various jobs to earn his living. In his later years he told his children that he had spent his boyhood in “the lake country.” At one time he kept company with a group of boys of dubious character. One night they decided to go into town for beer, and he suddenly realized that he had really been looking forward to that drink. Right then he decided not to go with that gang because he didn’t want to become a drunkard.

Jerome, sometimes referred to as J. J. on the records then kept, found work on the farm of Samuel Buchanan Frost in Fremont County, Iowa. The first time he went into the Frost home to eat, he saw sixteen-year-old Mary Angeline Frost and decided he would one day marry her. At that time he was only about eighteen years of age, and when he finally asked her to marry him the family had been snowed in for a week. Mary later said he just sat by the stove under her feet the whole week and hadn’t said a word. When he finally got up courage to propose, she decided she liked him well enough to marry him and was never sorry she told him “Yes.”

When they went to get married in January, 1854, the judge questioned his age, and Jerome was not sure of his birth year. His future father-in-law had gone with them to get married and pointed to Jerome’s full beard and told the judge that should be proof enough that he was an adult, so they were allowed to marry.

The first four of Jerome and Mary’s children were born in Fremont County, Iowa: Rebecca Jane, born on 2 October 1854 and died 1 May 1855; John Quincy, born 22 March 1856; Cora, born 27 December 1857 and died 27 August 1858; and William, born 6 September 1859 (LDS Archive Records).

In 1860 the family decided to go to California to get away from the Civil War that was fomenting. Jerome bought a new rope, intending to hang Brigham Young as they went through Utah. He told his family later that he had thought it would be a great service to mankind. When they reached Salt Lake City he heard Mormonism preached, was converted, and spent the rest of his life doing what President Young asked him to do.

Jerome and Mary lived for a while in Draper, where they were baptized. Their fifth child Martha was born in Cedar Valley, Utah, on 27 September 1861, and some months later Jerome was called to settle in Cache Valley in the northern part of Utah. Their sixth child Mary Frances was born in Richmond, Cache, Utah, on 27 August 1863, and the seventh child Jerome Jefferson, Jr., was born in Bear River, Box Elder, Utah, on 8 December 1865.

In 1867 they were called to go to the Muddy Mission in St. Thomas, Lincoln (now Clark), Nevada. There Jerome built a one-room adobe house and planted a grape vineyard. The St. Thomas LDS Branch records listed Jerome’s family in the 1868 Church Census, and gave their arrival date as November 1867. The census showed the family consisted of Jerome, his wife, and three sons and three daughters under the age of 14. The same record shows the 25 October 1868 blessing of a son Jerome, Jr. A fourth son, Foreman Eastwood Adams, was born in St. Thomas on 10 January 1870.

By that time they were practically starving due to poor soil, poor growing conditions, heat, dust, and insects. The settlers found life almost unbearable in that remote locality. Some of the land was so hard that their plows broke when they tried to till the ground. The soil in some areas contained so much alkali that nothing would grow. In other places they raised semi-tropical fruit and five crops of alfalfa per year; however, they soon discovered they had no market for the produce because of the distance from any other settlement. Some years the grasshoppers ate almost their entire crops. There were frequent sand storms which filled their irrigation ditches as fast as they could clean them out. The temperature during the summer of 1869 ranged from 115 to 125 degrees Fahrenheit; on the other hand, the temperature during the winter could fall as low as 20 degrees Fahrenheit.

To give the family some financial relief Jerome loaded a small wagon with grapes and set out to sell them, saying he would not come back empty-handed. That left Mary and the children rather stranded when the settlement broke up later that year and the inhabitants moved away.

After 18 months of absence, Jerome found his family in Spring City, Sanpete, Utah, where they had been moved at the insistence of Jerome’s father-in-law. As he had promised, J. J. returned with clothes, furniture, and money which he had accumulated on his trip.

The family remained in Spring City for several years, during which time Hettie Millicent was born on 23 November 1872, and Georgiana “Georgia” was born on 19 March 1874. Jerome’s daughter Mary Frances told her children that her father had been called to go to Washington County, Utah, in 1874 to help with the construction of the St. George Temple (Merrell Family Papers).

Jerome engaged in freighting as well as other activities until 1876 when he was called to take his family to the Arizona Mission on the Little Colorado River. The journey to their new settlement was one of great hardships. They made the trip from Utah to Arizona between February and April during all kinds of weather. As they traveled through Circle Valley Canyon, Jerome walked each day carrying a shovel to dig the wagon wheels out of the mud and chuck holes. In other locations there was deep snow through which to travel.

The Adams family settled in Brigham City, Arizona, sometimes called Ballinger’s Camp after the leader of their company. Their last child Wilford Woodruff Adams was born there on 11 December 1879. They lived in a closely-knit society in Arizona for several years.

Before the United Order was organized and their Articles of Agreement drawn up (Lake), the colonists worked unitedly to conduct their farming, sheep raising, lumber mill, grist mill, etc., in a cooperative-type operation. During construction of the dining room and large kitchen for the Order, Sunday meetings were sometimes held at the Adams’ home, as he was a counselor in the bishopric, the governing body of the settlement.

For the next few years Jerome was engaged in raising sheep and cattle as well as his other work assignments in the pioneer settlement. Late in 1881 he cooperated with brothers Charles and Edwin Whiting along with Sullivan Richardson in the purchase of what was called Brigham Fort, for $800. That was the remaining structure of Brigham City, which by that time had been abandoned by virtually all of the inhabitants (Tanner and Richards). There a ranching enterprise was conducted for a few years before the Adams family moved to Wilford, Arizona, where Jerome was the presiding elder of the local church group. He continued to pursue his livestock enterprise until 1889, when the family moved to Colonia Diaz, Chihuahua, Mexico.

Jerome took an active part in the community and church in his new-found home. Nearly everyone in Colonia Diaz called him “Grandpa Adams,” as he was quite a bit older than most of the other residents. They sought him for advice and appreciated his wisdom. He was proud to receive his Mexican citizenship from Pres. Porfirio Diaz on 28 April 1893.

Jerome was fond of music and played the bass drum in a band which took part in the celebration of all Mexican holidays in Colonia Diaz. One author wrote that he never missed a band practice though he had to ride his iron-gray horse one and a half miles to attend. Even in his advanced years he continued this activity.

He cherished his horses and took extremely good care of them, especially while he was freighting. When John W. Young was awarded a contract to construct a railroad from Deming, New Mexico, to Chihuahua City, Mexico, which would run close to all the Mormon colonies in the State of Chihuahua, a procession took place to celebrate the beginning of the venture. J. J. Adams was one of the men who paraded through town driving all the horse-drawn and mule-drawn vehicles to be used in carrying out the many aspects of the ill-fated project.

In 1895 when some additional land became available for purchase, J. J. was one of a group of Diazites who went into the cattle raising business, a return to the occupation he had formerly engaged in while living in Wilford.

Jerome was very clean in his person and with his clothing. He took pride in being a gentleman and was devoted to his family. He died peacefully in his sleep on 5 May 1902 at the age of sixty-seven, in Colonia Diaz. In the 1970s one of his great-grandsons, Robert Adams of Las Cruces, New Mexico, went to the Mexican Colonies and searched the cemetery in the ruins of the colony of Diaz until he found Jerome Jefferson Adams’ tombstone. By that time the Mexican people had destroyed most of the markers, but in a corner hidden by grass was the stone engraved with his name, death year, and a chiseled hand holding a Book of Mormon, his final testimony of the creed that governed most of his life.