George Godfrey

January 24, 1845 – December 31, 1926

|

Where are they going and what will they they do when they get there? They are going west to build a new home for themselves, for when their journey is through, it only begins. There is land to clear and homes to build. Settlements to establish and families to raise.

Life was hard. There were no conveniences, no easy way. Children were born and many died. Mothers were taken from their husbands and children in death. But sorrow and grief couldn't get in the way of pressing forward. Yet they were not dead. They lived on in heart and memory with hope of a grand reunion.

To them, they were surviving and persevering Taking life day by day, doing what had to be done. What was accomplished yesterday made life just a little bit better today. Hopefully tomorrow will be better still. Three steps forward and one backwards.

The days have become more than a century and a half now and life is better. Better ways of doing things. Better ways of living. Better because of the foundation they laid and that their children and grandchildren built upon. They are all gone now. But not forgotten for their legacy is our heritage.

Of the tens of thousands of pioneers who established the communities of the Territory of Utah, there are ten of thousands of stories of struggles and heartache. Yet there are tens of thousands of stories of courage, triumph, and success. This is just one of those tens of thousands of stories, it is the story of George Godfrey, a true pioneer.

George Godfrey, the oldest son of John and Mary Pittaway Godfrey, was born January 24, 1845 in Worcester, England. Obtaining employment at age four, he worked for a Mr. Bladham, using clappers to keep the sparrows and black birds from eating the grapes. For his labors he was given three pence a day. Reaching eight years old, George was hired by a Mr. Parker as an errand boy in the Stokes Salt Works where his father was employed. After running errands for eighteen months, George became an apprentice mason. Mr. Paxton taught him the trade that he worked at for three years.

George's family joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1848. George was baptized at the age of ten on April 14, 1855. Mormons were not very well accepted in England and the family struggled to make a living after his father was fired from his job for being a Mormon. Like most Latter-day Saints in England, John received the impression that he should leave England and join the Saints in Utah. He was advised by church leaders to send George, who had reached the age of sixteen, ahead of the rest of the family to prepare a place for them.

Charles W. Penrose, a native of London who later became an Apostle and First Counselor in the First Presidency, presided over the London Conference and often visited the Godfrey home and made it his headquarters whenever hew was in that part of England. It was no coincidence that George would be part of the company that President Penrose was in. George prepared to depart. Probably frightened, yet filled with anticipation, George bid his family farewell and boarded "The Monarch of The Sea," on May 13, 1861. At eleven a.m.on the 16th the great vessel weighed anchor and amid the cheers of parting friends, the ship left the wharf and began its long voyage . His was a unique adventure for a boy just sixteen years of age, traveling alone, with no family support.

A big three-decker, this clipper ship was exceptionally strong and fast and operated with the Washington Line out of New York. Built with the usual three masts, a round stern, and billethead, the Monarch of the Sea was built in 1854 and was two hundred and twenty three feet long and weigher 1,979 tons. After more than a quarter of a century in service the Monarch of the Sea was reported lost in 1880.

The Monarh of the Sea |

During the passage the Saints were organized into eleven wards and lived together harmoniously. Many of the immigrants in the company were Scandinavian. After about sixteen days at sea, the ship encountered a very bad storm that lasted for four days. The sailors were afraid that the ship would go down, and they prepared all the long boats (there were 6 of them in all) and at the same time swearing that no Mormon would get into any of the boats. The ship groaned as though it could not stand it another minute, so President Woodard called upon all the elders and went up on the deck. They prayed and rebuked the wind and waves, and in a short time the storm abated and all were saved.

Because of overcrowding in the singles quarters, their leaders encouraged those who were betrothed, to be be married immediately to free up some berths. Consequently there were eleven weddings, in addition to nine deaths, and four births on board the ship. After thirty-four days at sea the Monarch of the Sea dropped anchor on the 19th of June in New York Harbor. With the United States engaged in the Civil War, extra precautions were taken as the passengers disembarked to make sure that there were not any Confederate agents among the passengers.

From New York, George and the other immigrants destined for the Territory of Utah traveled by train to St. Joseph’s, Missouri. At that time the railroad went no farther west, so they had to go by steam boat up the Missouri River to Florence, Nebraska. He joined one of the many wagon trains that departed during July. It is probable that George came west in the Woolley Company. George recalled walking much of the way and carrying children across the Platte River on his back. He arrived in the Great Basin September 2, 1861.

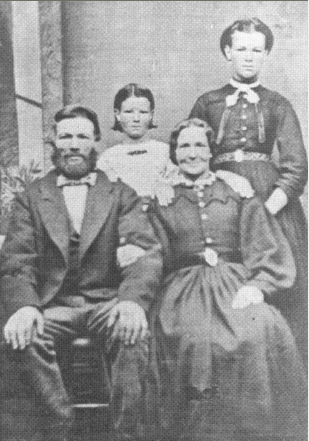

John and Mary Pittaway Godfrey. Behind them are Catherine and Sarah |

He obtained employment soon after coming to Salt Lake, when one job ended he secured another. The first winter he and his Uncle Richard hauled rock from the canyons for the Salt Lake Temple and theater. With the arrival of spring, George was employed to carry mail from Salt Lake City to Butte, Montana. Several times he was held up by bandits. He was good at handling teams of horses, and he learned from all of his experiences.

He had acquired a city lot and constructed a small log cabin on it. In addition he made a table and some chairs from logs hauled from the canyons. When his parents arrived on October 10, 1862, he was proud to show them their new home. The Godfrey family lived in Salt Lake City that first winter. Then they moved to Chalk Creek, near Coalville. His father John, hearing land was available in Cache Valley, moved to Clarkston, Utah in 1865. George did not go with them. Instead he moved back to Salt Lake City and again supported himself.

While living in the territorial capital, he first became acquainted with the Morris Gover family and their fourteen-year-old daughter Emily. Perhaps his attachment for her drew him back to the Tenth Ward once more. George and Emily courted for sometime and fell in love. George told of the time he walked all the way from Clarkston, where he had been to see his family, to Salt Lake City with the exception of a few miles when someone with a team and buggy gave him a ride. When he arrived, he went to see Emily. Emily had her heart set on going to a dance, so they went. George said he was stiff and sore, and tired but still managed to dance, and they had a great time.

When George asked Morris Gover if he could marry his daughter (a custom adhered to at that time), Mr. Gover asked George if he was sure she was the one he wished to marry. George said he toId him he hadn't had much time to look around, but he was convinced that she was the prettiest young lady he had ever seen, and the one he wanted for his bride.

Emily Gover |

Eleven months later their first daughter, Martha Ann (Annie) was born on October 22, 1866. A year and a half later on December 4, 1867, Emily gave birth to another baby girl whom they named Emily Sarah. She lived only eight months and was buried in the Salt Lake Cemetery.

George and Emily had an agreement that if they had an argument and Emily was still upset when George came home, he would throw his hat in the door first. If Emily threw it back out, he would know she was still upset. George said he never remembered her tossing his hat out.

Emily was a beautiful woman and much of the time adorned her hair with little nets accented with beadwork to keep her hair in place. She kept herself as well as her house spotless. Emily had flair for tatting and netting and she had a white quilt with a pink design that was a treasure to her. The Govers were neat, tidy people, "who had a place for everything and everything in its place." Emily was the same way.

In 1869 George and Emily moved to Newton in Cache Valley, where they lived for about a year. It was here that George Henry was born on December 17, 1869. He died when he was eight months old and his body was taken back to Salt Lake for burial in the same plot where his sister was interred. The parents were grief stricken with the loss of two babies at eight months of age.

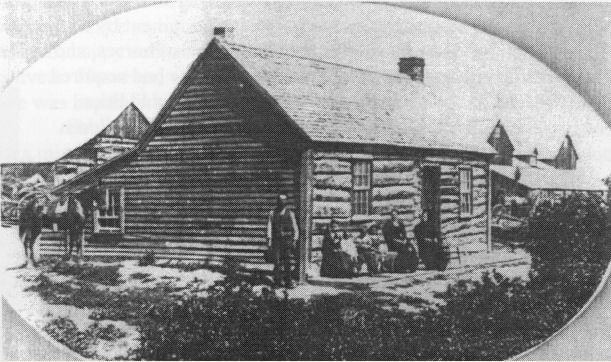

The George Godfrey home in Clarkston |

With the dawning of a new decade George and Emily had every reason to be hopeful. They had a new four-room log home, land, and were respected members of the community. There were, however, periods of sorrow as he and Emily continued to lose children in death. John William was born on August 28, 1871. He was a bright cheerful little boy, but passed away having only reached age four.

Joseph Maurice was born on June 3, 1874 and nearly a year and a half later Henry Morris, who went by Harry, was born on November 5, 1876. Sadie Emily was born on April 14, 1879. Annie Joseph, Harry, and Sadie all appeared strong and healthy.

George was personally acquainted with Martin Harris, one of the Three Witnesses to the Book Of Mormon. In 1874 Martin Harris moved to Clarkston with his son. The little white haired man was often seen on the streets of Clarkston. He freely bore his testimony to all who would listen. In 1875 he was stricken with paralysis and was confined to his home. George sat up nights with him during his last illness and gave the following testimony:

During the life of Martin Harris, one of the three witnesses to the Book of Mormon, I had ample

opportunity to become well acquainted with him, having met him for

the first time in Salt Lake City, Utah, near the year 1867, as my

memory serves me, and at that time considered it a privilege to shake

hands with a man who had had the experiences and the testimony which

he bore witness to.

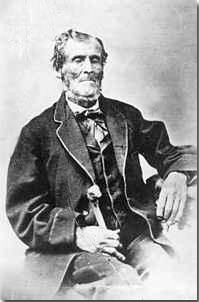

Martin Harris about 1870

Later, he moved to Smithfield, Cache County, Utah and later moved to Clarkston, same county, where he died in the year 1875. Prior to his death and in his last sickness I sat up nights with him in connection with my brothers John E. and Thomas Godfrey, both of whom now reside at Clarkston. They can both make affidavit to the things I am herein stating. Many times I have heard Martin Harris bear witness to the truthfulness and genuineness of the Book of Mormon, at times when he was enjoying good health and spirits and when he was on his deathbed. His testimony never varied. I have seen others, and I myself, try to entrap him relative to the testimony which he bore by cross questioning him relative to the scenes and events which are Church History in connection with the bringing forth of the Book of Mormon, and that upon all of these questions his mind was as clear as it is possible for the human mind to be. His testimony has left no trace of doubt in my mind that he actually conversed with an angel who bore testimony to him of the truthfulness of the records contained in the Book of Mormon, that he saw and handled the gold plates from which the records were taken.

A few hours before his death and when he was so weak and enfeebled that he was unable to recognize me or anyone, and knew not to whom he was speaking, I asked him if he did not feel that there was an element, at least of fraudulence and deception in the things that were written and told of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, and he replied as he had always done, so many, many times in my hearing and with the same spirit he always manifested when enjoying good health and spirits and said: “The Book of Mormon is no fake. I know what I know. I have seen what I have seen and I have heard what I have heard. I have seen the gold plates from which the Book of Mormon was written. An angel appeared to me and others and testified to the truthfulness of the records and had I been willing to have perjured myself and sworn falsely to the testimony which I now bear I could have been a rich man, but I could not have testified other than I have done and am now doing for these things are true.”

I prepared the grave and assisted in the burial of Martin Harris in the Clarkston graveyard where the remains now rest.

Martin Harris died on July 10, 1875 and is buried in the Clarkston cemetery. George was the sexton of the Clarkston Cemetery for many years and was directly involved with the preparation of the graves and the burials, including that of Martin Harris. Sometime during the 1880s, it was proposed to exhume the remains of Martin Harris and have them buried in Smithfield. The mere idea outraged the citizens of Clarkston who had cared for him during the last year of his life. To make sure that such a thing would never happen, George with the help of his sons Harry and Joe leveled off the grave and with a team of horses drug one of the huge stone steps from the old church and placed it over the grave. Needless to say, the grave remained. A large granite pillar now marks his grave and an annual pageant is held in Clarkston honoring the “Man Who Knew”. The stone can still be seen level with the lawn in front of the monument.

After having already lost three children, tragedy struck the Godfrey home once again. Emily gave birth to a daughter on November 12, 1881, whom they named Mary Rose. The baby passed away on the day she was born. Emily suffered for two weeks from complications associated with this birth. Then her condition worsened and she died on November 26, 1881 – their sixteenth anniversary. Mary Rose's small coffin was placed on top of her mother's bier, and both were buried in the same grave.

Emily and George had a happy marriage during the brief sixteen years they were together. Out of eight births only four children lived to adulthood. George kept a small trunk belonging to Emily that contained a few of her little trinkets. Often he would be found holding the trunk, looking inside and reminiscing. Following Emily's death George constructed a barn with three distinct peaks on top to symbolize the letter "E" to stand for Emily.

George was left with four children, ages fifteen, seven, five, and nineteen months. He knew unsatisfied grief. The burden of caring for the family fell on Annie's fifteen year-old shoulders. Nine months passed, and perhaps she grew weary of the load she carried, or perhaps her love for Alfred Sparks was too strong to be denied. For whatever the reasons, Annie eloped with Alfred, and they were married September 9, 1882. Annie was not quite sixteen year of age. The other three children were much younger. Times were hard and George worked hard to support his family. He was terribly lonely, depressed and discouraged. With Annie gone, George's younger sister Catherine, who was nineteen years old at the time came and helped for a while.

George had a dream one night in which he saw a beautiful young lady. He somehow knew that she would become his wife. Not many days following his impressive dream, a friend, Casper Loosli, told George about a young Swiss immigrant, Elizabeth Zaugg, who lived in Providence, Utah. George traveled there and met Elizabeth. He recognized her as the girl in his dream. He offered her a job tending his children, to which she gave her consent.

Elizabeth was so good with the children and worked to care for the home. She had a beautiful voice and soon won the love of the family and especially George. George and Elizabeth were married in the Salt Lake Endowment House on the first of March of 1883. She was twenty two and he was thirty eight. Elizabeth was the daughter of Johannes and Barbara Leighti Zaugg and was born on March 10, 1862 in Bern Switzerland. Her family were converts to the church and immigrated to America when she was a teenager. George and Elizabeth were the parents of nine children: George John (21 Mar 884), Mary Barbara (13 Aug 1885), Elizabeth Letitia (14 Nov 1886), Albert Matthew (10 Apr 1889), Catherine Esther (17 Jun 1892), William Gover (27 Apr 1894), Brigham Wilford (25 Jan 1897), Etta Lucetta who was known as Ettie (7 Jan 1899), and Reuben Leo (24 Apr 1901). All of who were born in Clarkston

George had great admiration for the authorities of the Church. He walked from Clarkston to Salt Lake City many times to attend General Conference. He was personally acquainted with all the leaders of the Church. He held the office of a High Priest.

Plural marriage was a common practice in the Church and after George had a thorough discussion with Elizabeth, she gave her consent for George to take a second wife. He then married Eliza Maria Pack, a young woman from Northampton, England on July 6, 1888. Eliza was the the daughter of Benjamin and Maria Holton Pack. She was born on July 23, 1868 in Northampton, England. After the death of her father the family came in contact with the missionaries. In August of 1884 Eliza, her mother, and brother and sisters were baptized. In 1886 they immigrated to America and made their way to Clarkston, the home of one of the missionaries who had baptized them.

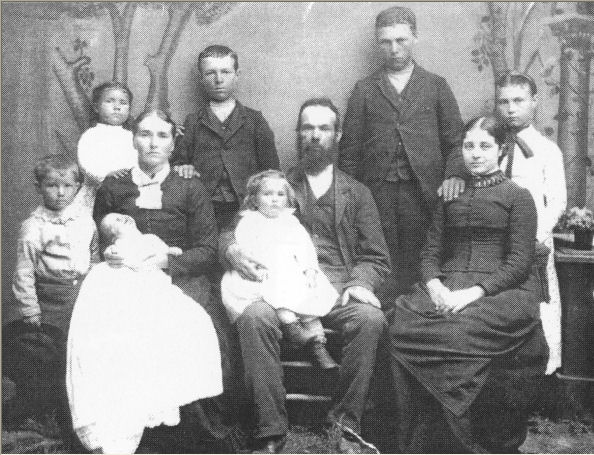

| The George Godfrey Family - 1889 Standing: George Jr, Barbara, Harry, Joe, and Sadie. Seated: Elizabeth Zaugg holding Albert, Joe with Lettie on his lap, and Eliza Pack. (George Jr., Barbara, Albert, and Lettie are the Children of Elizabeth. Harry, Joe, and Sadie are Emily's children. Eliza hadn't had any children by the time this photograph was taken. |

When Eliza married George, she was twenty years old and George was forty three. They were the parents of eleven children: George Orson (19 Sept 1890), Emily Maria (23 Dec 1892), Hyrum Heber (7 Jul 1895), Chloe Hazel (2 Aug 1897), Nettie Eliza (19 Dec 1898), Beatrice Louise (13 Feb 1901), Samuel (23 Mar 1903), Cyril Seymour (11 Feb 1904), Asael Oriel (3 Jul 1906), Newel Taft (13 Feb 1909), and Florence Lavon (5 Jul 1912). Emily, Chloe, Samuel, and Newel died in infancy. All were born in Clarkston except Florence who was born in Fielding.

Elizabeth accepted Eliza into their family and welcomed her into their four room log home where they all lived together for a few months. Eliza had a small room for herself and her belongings. Later, George built a frame two story house for each of his wives, just one block apart. Elizabeth and Eliza were very much like sisters and would shed a few tears at parting when they visited each others homes.

In October 1890 the Manifesto was issued by the First Presidency which ended authorization of any new plural marriages. However, it had no effect on the status of already existing plural marriages.

The SS Wyoming |

George was very civic minded and was one of the great pioneer leaders in Clarkston and Cache County. He was prominent in both Church and political affairs. He saved many lives by his quick thinking and expert judgment when called to help with the sick and afflicted. He, along with four others, chose the location where the cemetery now stands and served as the sexton until April 1910.

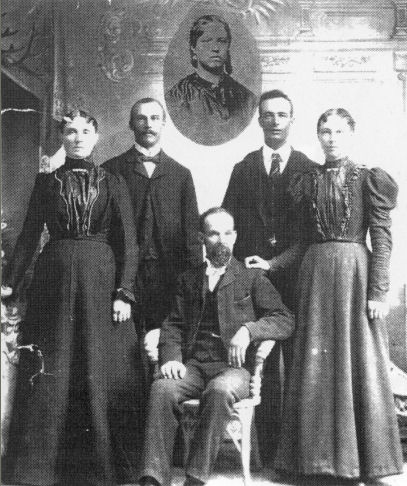

The sons and daughters of George and Emily Godfrey. Left to Right: Annie, Joe, George, Harry, and Sadie.Insert: Emily Gover. |

On April 27, 1910 he moved to Fielding with Eliza. Elizabeth and her children remained in Clarkston. In Fielding he purchased more farm land. They had a large orchard and lots of small fruit which they willingly shared with relatives and friends. He always treated rich and poor alike. He had a great love for the Indians. He had a beautiful singing voice. He was a good carpenter and built many homes, sheds, barns, and bridges. He had many horses, cows, pigs, and chickens. He raised lovely gardens and had cellars full of produce for winters. He continued to be active in the community in Fielding where he served as mayor and was the janitor at the Fielding School house.

Elizabeth, who was still living in Clarkston, died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of fifty five on March 19, 1917. Five of her nine children were still unmarried at the time of her death.

George died on December 31, 1926 in Fielding at the age of 81 years 11 months 7 days. He was buried at Clarkston on January 3, 1927. George Godfrey was a true pioneer and a leader among his peers. Most importantly he was a husband and a father. Eliza died on Christmas Day in 1961 at the age of ninety three. She too is buried in the Clarkston cemetery.

The main source for this story came from George Godfrey's History, by Kenneth Godfrey and the life sketch of George Godfrey by his daughter, Florence G. Munson. History of Clarkston: The Granary of Cache Valley. Details of his mission are from the Latter-Day Saints' Millennial Star, Volume 53. Details about the Monarch of the Sea: Ships, Saints, & Mariners — A Maritime Encyclopedia of Mormon Migration 1830-1890, Conway B. Sonne, 1987. Information about crossing the Atlantic Biography of William Riley and Hussler Ann Probert Stevens, comp. and ed. by Orvilla Allred Stevens (privately printed, 1981) pp. 5