Margaret Spaulding

1 April 1822 – 10 August 1863

|

Together they raised a large family of fourteen children. The first died as a small child of two. Their oldest daughter, Margaret, who was born on April 1, 1822, was no doubt a tremendous help in taking care of such a large family. When Margaret was twenty three years old her mother died.

During the course of time she became acquainted with a young shoemaker from Blairgowrie by the name of David Buttar. After a proper courtship, they were married on March 14, 1848 at the home of her parents at Myreside Farm. David and Margaret made their home in Blairgowrie where he continued his work as a shoemaker. Their first child, Marjory Meek was born on September 16, 1849 in Blairgowrie.

Sometime in 1849 or 1850, David became acquainted with missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and listened to their message. Over the course of time, his interest deepened and he soon became convinced of the the truthfulness of the their message. He was baptized the January 19 , 1851 by Thomas Frazer and confirmed a member of the Church ten days later by William Burton. Margaret was not as quick to embrace the new religion.

She was expecting a baby when David was baptized. Toward the end of May, a woman by the name of Elizabeth Graham MacDonald came to live with David and Margaret. Only a few days earlier she had married Alexander Findlay MacDonald. Alexander, who was a native of Scotland, was serving as a missionary in the British Mission at the time. As he was sent north to the Scottish Highlands, he had made arrangements with David for Elizabeth to stay with them. David thought she might help bring Margaret to an understanding of the gospel.

Being a typical man, he neglected to inform Margaret of the arrangement which caused some embarrassing circumstances. However, just before he left, Alexander explained the arrangement to Margaret because he did not wish to leave without acquainting her with the fact. Margaret chided David for having failed to inform her at first; she declared that Elizabeth must remain with her. That eased the tension that had existed.

During her stay, Elizabeth was of tremendous assistance to Margaret. Her baby, who they named Bethea after David's mother, was born on June 25, 1851. David employed and boarded about fifteen people in his business, thus making the household labors arduous. Elizabeth took on most of these labors.

By the time that

Elizabeth's husband returned in November, Margaret's interest in the

church grew until she too accepted the message of the restored

gospel. She was baptized on November 15, 1851 by Alexander Findlay

McDonald and was confirmed on 16 November 1851 by John McNaughton.

Myreside Farm

After about a year, David and Margaret began to make plans to immigrate to America and gather with the main body of the Church in Utah. Her family was very much against them joining the church to begin with. Her brothers told her that if she would leave the Church and her husband and remain in Scotland, they would take care of her and her three children. Her family was well off, financially, and could have given her a life of ease, but Margaret loved the gospel, and her husband, and would not accept their offer. Because of her decision she was cut off from her family.

With Margaret expecting their third child, they waited until after little David was born on December 23, 1853 to leave. In the process of immigrating, they first needed to apply for passage with the Church's agent in Liverpool. When a sufficient number of applications were on hand, the agent chartered a vessel. David and Margaret would have been notified by circulars, containing instructions to them on how to proceed, when to be in Liverpool to embark, also stating the price of passage, the amount of provisions allowed, etc.

With the arrangements made, they got their affairs in order. As soon as Margaret and the baby were ready to travel, they packed up what belongings they could take with them, including David's tools. After bidding farewell to family and friends, they left Blairgowrie and Scotland, never to return again. They made their way to Liverpool, England most likely by railroad.

Once in Liverpool, Margaret, David, and their three children, would have reported in with the agent. It was generally agreed that the passengers should go on board the ship on the day of their arrival in Liverpool. In their case the ship was the John M. Wood, a 1,146 ton sailing vessel, under Captain Hartly. In all, three hundred and ninety three immigrants, including fifty eight from Italy, reported aboard the John M. Wood. When the passengers were on board, the agent, who was generally the presiding officer of the Church in the British Isles, would visit them and proceed to appoint a committee, consisting of a president and two counselors. They were received by the emigrants by a sustaining vote and implicit confidence was placed in them. Elder Robert Campbell was President of the Ship’s Company with Elder Jabez Woodward and Elder Alexander F. McDonald as his counselors.

The presidency then proceeded to divide the immigrants into eight wards. An Elder or Priest, with his assistants, presided over each ward. Watchmen were then selected from among the adult passengers, who, in rotation, stood guard day and night over the ship until the ships departure to watch out for stowaways.

The ship set

sail on Sunday, March 12, 1854. The weather was

very rough in the Irish Channel and for the first six days at sea.

After that, the weather was favorable for the rest of the voyage.

Once at sea, the presidents of the various wards saw that the

passengers arose about five or six o'clock in the morning, that they

cleaned their respective portions of the ship, and threw the rubbish

overboard. This attended to, prayers were offered in every ward,

after which the passengers prepared their breakfasts, and during the

remainder of the day they could occupy themselves with various duties

and amusements.

The ship set

sail on Sunday, March 12, 1854. The weather was

very rough in the Irish Channel and for the first six days at sea.

After that, the weather was favorable for the rest of the voyage.

Once at sea, the presidents of the various wards saw that the

passengers arose about five or six o'clock in the morning, that they

cleaned their respective portions of the ship, and threw the rubbish

overboard. This attended to, prayers were offered in every ward,

after which the passengers prepared their breakfasts, and during the

remainder of the day they could occupy themselves with various duties

and amusements.

In addition to this daily routine, when the weather permitted, meetings were held on Sundays, and twice or three times during the week, at which the usual Church services were observed. Schools for both children and adults were also frequently conducted.

At eight or nine o'clock at night prayers were again offered and all retired to their berths. Such regularity and cleanliness, with constant exercise on deck, were an excellent benefit to the general health of the passengers, a thing which has always been proverbial of the Latter-day Saints' emigration.

Each

adult received a weekly ration, with half the amount for children

between fourteen years and one year old, which consisted of two and a

half pounds of bread or biscuit (to the British, biscuit is a small

and hard, often sweetened, flour based product) one pound of wheat

flour, five pounds of oatmeal, two pounds of rice, a half pound of

sugar, two ounces of tea, and two ounces of salt. Each passenger was

also allotted three quarts of water daily.

In addition to the

above, the Latter-day Saints were furnished with two and a half

pounds of sago (a starch extracted from the pith of sago

palm stems), three pounds of butter, two pounds of cheese, and one

pint of vinegar, one pound of beef or pork weekly to each adult was

substituted for its equivalent in oatmeal for the voyage. This

quantity of provisions provided enough for the passengers to live

during the voyage.

Passengers furnished their own beds and bedding, and likewise their cooking utensils such as a boiler, saucepan and frying pan; also a tin plate tin dish, knife and fork, spoon and a tin canister, or an earthen one encased in wickerwork, large enough to hold three quarts of water, for each person.

As the voyage proceeded, all went well. On April 6th, it being the twenty fourth anniversary of the organization of the Church, they held a Conference on board and the President of each ward reported on the condition of his ward. But the voyage turned to sorrow on the 12th of April for Margaret and David, as little David, who was only three and a half months old died. They would have liked to have kept his tiny body aboard the ship for the remainer of the voyage and have him buried on land. But that was not possible as they were still three weeks from their destination. A small wooden coffin was made for him, and the next day a memorial service was conducted for him and his body was committed to a watery grave. With tear filled eyes and saddened hearts, they watched his coffin splash into the water and sink beneath the waves of the Atlantic Ocean. In addition to little David, there were three other children and two adults who died on board during the voyage. On the other hand, two children (twins) were born, one couple married, and one person baptized.

On the 22nd of April a tea party or dinner was held. In seating the Saints for this meal, it was necessary to seat them two wards at a table. Afterwards singing and a theatrical performance was enjoyed.

After seven weeks at sea, the John M. Wood arrived in New Orleans on May 2nd. The provisions that were not consumed, were given to the passengers on their arrival at New Orleans, instead of being returned to England as in the case of other emigrants ships. The ship had made a quick passage and the amount of provisions saved was one hundred and fifty pounds of tea, nineteen barrels of biscuit, five barrels of oatmeal, four barrels and four bags of rice and three barrels of pork.

On arrival at New

Orleans, the emigrants were received by an agent of the Church

stationed there for that purpose. He had procured a suitable

steamboat for them to proceed on to St. Louis, Missouri, without

delay. It was the duty of this agent, furthermore, to report to the

agent in Liverpool, the condition in which the emigrants arrived, and

any important circumstance that might be to his advantage to know.

While registering with the government officials in New Orleans, David

added an “s” to Buttar and went by Buttars ever since. The

passengers shifted their belongings to the river steamboat “Josiah

Lawrence”. The trip up the Mississippi River took another twelve

days.

On arrival at New

Orleans, the emigrants were received by an agent of the Church

stationed there for that purpose. He had procured a suitable

steamboat for them to proceed on to St. Louis, Missouri, without

delay. It was the duty of this agent, furthermore, to report to the

agent in Liverpool, the condition in which the emigrants arrived, and

any important circumstance that might be to his advantage to know.

While registering with the government officials in New Orleans, David

added an “s” to Buttar and went by Buttars ever since. The

passengers shifted their belongings to the river steamboat “Josiah

Lawrence”. The trip up the Mississippi River took another twelve

days.

From St. Louis the emigrants were transported by another steamboat up the Missouri River to the staging area at Westport, Missouri at Kansas City, in Jackson County, twelve miles west of Independence. At these outfitting places the emigrants found their teams, which the agents had purchased, waiting to receive them and their luggage.

Ten individuals were allotted to each wagon along with one tent. They were allowed one hundred pounds of luggage, including beds and clothing, for each person above eight years old; fifty pounds to those between eight and four years old; none to those under four. A full team consisted of one wagon, two yoke of oxen and two milk cows. The tents were made of a very superior twilled cotton procured in England. It was generally supplied to the emigrants before their departure from Liverpool, and they made their tents and covers on the voyage, and thus saved expense.

Each wagon was supplied with one thousand pounds of flour, fifty pounds of sugar, fifty pounds of bacon, fifty of rice, thirty pounds of beans, twenty pounds of dried apples and peaches, five pounds of tea, one gallon of vinegar, ten bars of soap, and twenty five pounds of salt. This was supplemented by the milk from the cows, the game caught on the plains and pure water from the streams. The emigrants who had the means, of course, purchased what they pleased, such as dried herrings, pickles, molasses, and more dried fruit and sugar.

The Saints used all kinds of wagons, but mostly they used ordinary reinforced farm wagons, which were about ten feet long, arched over by a waterproof canvas that could be closed at each end—almost never the huge, lumbering Conestoga wagons seen in Hollywood movies. Because the wagons had to cross rivers, the bottoms were usually caulked so they would float. While the covered wagons of the era may not have been ideal for travel (they were uncomfortable to ride in, broke down, were slow and cumbersome), they were the most efficient means of hauling goods. Families en route could live in, alongside, and under these ox-drawn mobile homes, and at the end of the trail, they could become temporary homes until real houses could be erected.

Oxen were preferred over horses because of their ruggedness and strength. Besides, the Indians were not interested in them.

Margaret and David were assigned to the William A. Empey company. Captain Empey knew the trail well as he had been part of the Vanguard Company that crossed the plains with Brigham Young in 1847. On July 14th, the night before getting on the trail, A council weeting was held with Captain Empey presiding, it was resolved that Brother Robert Campbell would be president of the company with Brother Richard Cook as his First Counselor and Brother Woodard as the Second Counselor. Brother Charles Brewerton was to be the wagon master and captain of the guard. Three Captains of Tens were appointed and Brother Thomas Sutherland was named the clerk and historian of this company. The Captains of Ten and the wagon master were each responsible for roughly ten wagons.

The following rules rules and regulations were to be adhered to: That no gun shall be fired within fifty yards of the camp under a penalty of one nights guard duty. That the captain of each ten shall awaken the head of every family at four o'clock in the morning and be ready to roll out at seven, if circumstances will permit. That all were to go to bed at nine o'clock in the evening. That every man from sixteen to sixty years of age be eligible to stand guard. The above resolutions were laid before the whole company in camp and received their unanimous sanction. The next morning, forty three wagons pulled out of camp and headed west.

The basic trail routine, more or less observed, might be summed up as follows: arising, praying, cooking, yoking up, pulling out, "nooning" (when people ate [usually cold] lunches and draft animals rested and grazed), pushing on, selecting camp, gathering fuel, cooking, washing up, mending, recreating and socializing, rounding up stray livestock, milking, grazing the animals, praying, retiring, and standing guard. To this routine should be added washing, repairing wagons and equipment, hunting, dealing with Indians, conducting or attending religious services, and occasional births, accidents, sickness, deaths, funerals, marriages, and quarrels.

The emigrants walked beside the wagons as the made their way west. Only the sick or the infirm rode in the wagons, as they were loaded with belongings and supplies. On average, they covered a distance of ten to twelve miles a day. Along the trail there were several streams and rivers to cross. At the smaller streams, they waded across. At some of the major river crossings, they were ferried across by rafts. As they traveled westward, they marked their progress by the landmarks they passed. Places such as Fort Kearney, Chimney Rock, Devil's Gate, and Fort Bridger.

Injury, sickness, and death were commonplace. Emigrants suffered cuts; broken bones; gunshot wounds; burns; scaldings; animal, insect, and snake bites; stampedes; overturned wagons; shifting freight; drownings; quicksand; black scurvy; black canker (probably diphtheria); cholera; typhoid fever; ague; quick consumption (tuberculosis); headaches; piles; mumps; asthma; inflammation of the bowels; scrofula; erysipelas; diarrhea; small pox; itch; and infections of all kinds, including puerperal fever, which can follow childbirth.

Emigrants were also plagued by mosquitoes, chiggers, ticks, lice, gnats, bed bugs, fleas, flies, and other vermin. To these trials must be added the weaknesses of human beings under stress, which sometimes led to abusive language, fighting, quarreling, divorce, stealing, selfishness, sponging, excessive harshness, and alcohol abuse.

Although oxen moved very slowly, there was no quick way of stopping them. Therefore, many women, because their long skirts got caught, and were injured when dragged under animals or wagon wheels. Children often fell under the animals or wagons. Emigrants were also stepped on, gored, and kicked by animals.

Also, because emigrant trains moved so slowly, emigrants, especially children, occasionally got lost. This was the result of straggling, gathering flowers or berries, hunting, attempting short cuts, or trying to visit landmarks that were farther away than they appeared because of the clarity of the high plains' atmosphere. Most found their way back (some were helped by Indians), but some never were seen again in spite of searches, rifle shots, and signal fires.

Weather was also an important cause of discomfort and death. Emigrants suffered from exposure to heat, mud, wind, rain, cold, snow, and blizzards. Some were hurt and even killed by lightning.

Funerals and burials were often hurried affairs, as little time could be spared while en route. Shallow graves were dug, unless the ground was frozen, in which case, no grave could be dug. (In cold but not yet freezing weather, the preferred place to dig a grave was the site of the previous night's campfire.) A few were buried in coffins, many others only in blankets, hollowed out logs, or between pieces of bark. Children were often buried in containers like bread boxes and tea canisters. Some graves were marked, but more often everything was done to obliterate all traces of the grave, to discourage wild animals (and sometimes Indians) from digging up the corpse.

The problem of privacy for the purposes of elimination was solved by following the common rule: men to one side, women to the other. If the women went in a group, several sisters standing with skirts spread wide could provide a privacy screen for each other. Most wagons also had chamber pots.

Margaret's family were not immuned from the hardships of the trail. At one point, cholera broke out in the company. David came down with it quite bad, nearly dying from it. It took some time for him to get over it.

One day when they had camped for the night, David had gathered up some firewood. As he dropped his bundle onto the ground, a rattle snake slithered out of his pile of wood. He must have carried it some distance in his arms but it did not hurt him. Another time he made his bed down under the wagon. In the morning after he had dressed himself and went to roll up the bedding, he found a rattlesnake curled up in the bedding; he had slept with it all night, and again it had not hurt him.

The journey came to an end on October 15, 1854. After three months on the trail and seven months after leaving their home is Scotland, Margaret, David, and their children arrived in Salt Lake City. There they met Brother Samuel Mulliner. Brother Mulliner was from England and had been a missionary for the Church in Scotland; he had settled in Salt Lake City in 1850. He hired David to work at making shoes for him. David and his family only stayed in Salt Lake City for a few months. In January 1855 they moved to Lehi, Utah.

At the time, most of the homes in Lehi were commonly adobe and log houses with mud thatched roofs and dirt floors. This is the type of home that David and Margaret would have lived in. There was a schoolhouse with a fire place in one end to keep the interior warm. For seats, the children used rough slab benches without backs. Other furniture in the room consisted of a long· table where the pupil practiced writing. Books were rather scarce but they managed.

It was in 1854 and 55 that the amusement loving nature of the people took definite form in the organization of the first dramatic association of Lehi; and on February, 16 1855, soon after David and Margaret and their two children arrived, two productions were given: "Priestcraft in Danger" and "Luke the Laborer." Tallow candles were used for foot lights, wagon covers, painted with charcoal and red paint, the latter from the hills above Lehi, formed the scenery and drop curtains. The people who settled in Utah were people from many countries and brought their talents with them.

During the fall of 1855, Margaret received the news from Scotland that her father had passed away on August 20th.

The winter of 1855-56 was one of the most severe in the history of Utah. The people suffered intensely at this time. Heavy snows and extremely cold weather continued until late in the spring. With a small store of food owing to the failure of crops the year previous the people were subjected to deep and prolonged suffering. Margaret and David faced these problems the first year they were in Lehi. It was on May 22, 1856 that a baby son was born to Margaret and David. They named him John Spalding Buttars.

David continued making shoes for Samuel Mulliner. He did not have a team and wagon, so he would walk to Salt Lake City to get the leather and return his finished shoes, then walk back, a distance of thirty miles each way. The road at the Point of the Mountain was excessively steep and difficult to travel.

After a year or two in Lehi, David raised a team of oxen from calves and began to do a little farming. That year there was a serious infestation of Mormon crickets that destroyed the crops. The settlers tried everything to destroy them. Everyone, men, women and children, worked hard to get rid of them. They dug ditches and filled them with water, and drove the crickets into them; they scattered straw over the fields and when these were covered with insects they set them on fire; they dug holes in the ground, brushed the “iron clads” into them and covered them with earth. But all of their work seemed futile; they were unable to perceive that the number of the creatures had diminished in the slightest.

There was no flour in Lehi that year. They ate bran bread and clabber milk. Clabber is a food produced by allowing unpasteurized milk to turn sour at a specific humidity and temperature. Over time the milk thickens or curdles into a yogurt-like substance with a strong, sour flavor.

It was during the winter of 1857-58 that the Saints were ordered to leave Salt Lake City and move south because of the coming of Johntson's Army. Accordingly, Brigham Young directed all of the people north of Utah County to leave their homes and proceed southward, Thus began the "move" in which Lehi played an important role.

During the spring of 1858 thirty thousand people migrated southward. The people of Lehi helped these people with wagons and teams. Every home in the little town was thrown open and each room was filled to its capacity. David and Margaret would have been among those to open their hearts and their doors to these church members in need. That fall, Daniel was born on September 22, 1858

With time, conditions in Lehi improved. Robert Souter was born on April 6, 1861. Margaret had lived in Lehi eight years now, suffering through these many troubles, as well as the joys along the way. The joy of a good husband and her five children, ages fourteen to two years old. She was now expecting another child – this child was born on August 5, 1863. Margaret passed away five days later at the age of forty one. The baby, who they named Margaret, lived until August 21, 1863. Both mother and baby were buried in the Lehi Cemetery.

It would be interesting to know Margaret's feelings as she traveled through life. She gave up the life she knew in Scotland for the gospel she embraced. She did not have an easy life – she had to make hard decisions, face opposition, lose love ones, and face starvation. One can only speculate how she must have felt. But we must remember that Margaret understood the principles of the gospel and knew that this life was preparatory to a far greater one. She knew that her Father in Heaven loved her and accepted her sacrifice and her willingness to be obedient all of her life.

David eventually remarried and moved to the new community of Clarkston, in Cache Valley were he became very a successful and prominent citizen. He died on November 23, 1911. Margaret's surviving children grew up and married and raised families of their own with a posterity totaling forty one grandchildren.

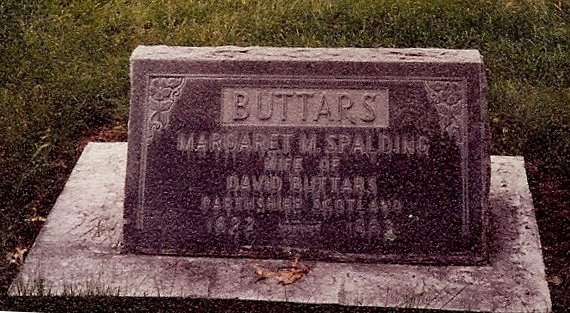

The orginal headstone that marked Margaret's grave (above) was destroyed and eventually replaced with a new headstone (below) by her grandchildren.

Sources:

The life story of Margaret Spaulding Buttars, written by Archulious B. Archibald and other uncredited sources.

The journal of Elizabeth Graham MacDonald

The Life Sketch of Henry Rampton (A n immigrant who sailed on the John M. Wood.)

"Mode of Conducting the Emigration" by church historian Andrew Jenson which first appeared in the LDS periodical, The Contributor, Volume 13 (1892) pages 181-185. (With details specific to the John M. Wood.)

Mormon Pioneer: Historical Research Study, Chapter 2: THE TRAIL EXPERIENCE: THE GREAT TREK: GENERAL COMMENTS (With details specific top the William A. Empey Company.)